I read last week's Observer New Review ("We need to teach our kids to code") with interest and admiration. In Britain, the debate about the teaching of computer science in schools is moving fast and in the right direction.

Last summer, I delivered the MacTaggart lecture at the Edinburgh International Television Festival. In an hour-long speech about the future of broadcasting, it was a minute or two about the state of computer science education that hit the headlines and seemed to hit a raw nerve.

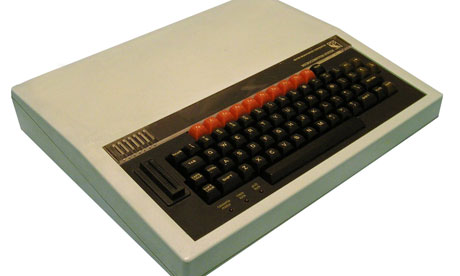

The problem, I argued, was that Britain risks throwing away its great computing heritage – from Bletchley Park to the BBC Micro – by failing to invest in proper computer science education. I was flabbergasted to learn that computer science wasn't being taught as standard in British schools. The Information and Communication Technology (ICT) curriculum was all too often teaching children how to use software products such as word processors and spreadsheets, but giving no insight into how that software was created.

Over the last decade, the number of people studying computer science in the UK has fallen by 23% at undergraduate level and by 34% at post-graduate level. Computing as an academic subject represented less than half of 1% of A-levels taken in 2011 – that's only 4,000 students.

Just seven months later, I'm amazed at how much the climate has changed. Following valuable recommendations in the Next Gen. report, from the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (Nesta), on the video games industry and the Royal Society report on computing in schools, in January the education secretary, Michael Gove, took the bold step of scrapping the existing ICT curriculum, freeing schools to teach a richer mix of programming, computer science and advanced IT instead.

The Observer's ongoing campaign, the Guardian's campaign on digital literacy and the work of organisations such as the British Computer Society and Computing at School have made concrete, practical contributions to the debate. An innovative start-up called Decoded is offering workshops aimed at teaching business people and students the basics of coding in just one day. The timely arrival of the cheap, accessible Raspberry Pi computer holds the promise of a new generation of youngsters learning to write code not seen since the days of the great BBC Micro, which helped launch the careers of so many of Google's British software engineers. It's worth noting that only 2% of Google's software engineers tell us they weren't exposed to coding at secondary school.

Of course, a great deal of work remains to be done to put in place a viable computer science curriculum. The course work doesn't yet exist and there is a severe shortage of teachers adequately equipped to teach the subject. And while industry must play its part in helping to shape this new curriculum, it cannot and should not seek to dictate it. Quite simply, the issues at stake are too important for that. Here's why.

As the Observer also reported last week, the same debate about computer science education is starting to emerge in many countries around the world. There is a growing recognition that technology will play a decisive role in the future well-being of our economies and societies. There is an urgent, global need for a better understanding of that technology.

Last year, the population of the world reached a new record 7 billion, but the number of people online reached only 2 billion. For most people on Earth, the digital revolution hasn't even started yet. Within the next 10 years, all that will change. There will be great improvements in the digital infrastructure of the developing world – wired networks will get faster and go farther. The smartphone revolution will be universal. Within 12 years, handsets are going to be 20 times faster; phones that cost $400 today will be available for around $20.

In that world, there will still be elites, but they will no longer have a monopoly on progress and opportunity. People everywhere will become more resourceful – anyone will be able to start a business, a news outlet or a school from their hut or caravan. Technology will be a great leveller and those countries that can equip their young people with the tools to master it, rather than simply to use it, will thrive.

That race is already well under way. To understand the scale of the challenge, and the opportunity, you need only consider that India is currently engaged in precisely the same debate about teaching computer science as standard to its tens of millions of secondary-school pupils. It's already mandatory in some top-tier schools. Imagine how many of those pupils will go on to become world-class software engineers and technology entrepreneurs. Then think again about the 4,000 British students taking computing at A-level.

The better news is that Britain sets out on this path with a number of inbuilt advantages. The recent Boston Consulting Group study showed that the internet contributed more than £120bn to the overall UK economy in 2010, more than 8% of GDP, well ahead of its main European competitors. That will rise to £225bn by 2016, more than 12% of GDP.

The government is doing the right thing in seeking to make Britain the technology centre of Europe by encouraging a new generation of start-ups, for example in its East London Tech City cluster. The Observer and many other organisations are right to give the issue of computing in schools such prominence and urgency. It is not an exaggeration to say that Britain's future economic and social prospects will depend upon it.

Google is pleased to add its support to the Observer's manifesto for rebooting the computing curriculum in British schools. We are committed to playing our part by seeking to inspire children to get involved in coding and by supporting excellence in computer science teaching. Indeed, we would go even further and say: let's get the whole world coding.