In 2005, the director Kevin Macdonald was working in Uganda on his film The Last King of Scotland. In the slums of Kampala he was struck by a curious fact. There seemed to be images of Bob Marley and "Get up, stand up" slogans and dreadlocks wherever he went.

Marley had been on Macdonald's mind anyway: he had been asked by Chris Blackwell, founder of Island Records, if he would be interested in getting involved in a film project about the Jamaican musician's enduring legacy.

The original plan had been to follow a group of rastafarians on their journey from Kingston to their spiritual homeland of Ethiopia, to attend a celebration of the 60th anniversary of Marley's birth. As it worked out, that film was never made, but, when the opportunity arose for Macdonald to make a more ambitious documentary about Marley, he jumped at the chance.

Crucially, the film had the blessing and support of the Marley family and key figures in his musical evolution, including the long-estranged original Wailer, Neville "Bunny" Livingstone. "It seemed very important to make this film now, while some of the people who had known Bob the best, in the early years in particular, were still around to tell the tale," Macdonald says.

He set about collecting interviews and researching some of the more mysterious aspects of a much mythologised life, that ended tragically prematurely in 1981, with Marley aged only 36.

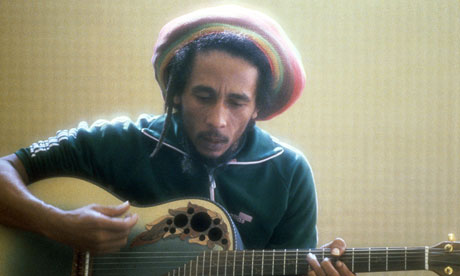

There were frustrations for Macdonald, not least the almost complete absence of footage or photography from the formative years of Bob Marley and the Wailers. But, with persistence and the rich memories of the period from Livingstone, Marley's widow Rita and others, he pieced the biopic together.

In his lifetime Bob Marley was a reluctant interviewee. "Having little formal education," Macdonald suggests, "he felt uncomfortable being asked questions by journalists." Anyway, there were aspects of his past on which he did not want to dwell, particularly his feelings about his white, absent father, Norval Marley, a man who claimed to have been a captain in the colonial Caribbean army, but wasn't.

In some ways, in the film, "Captain" Norval becomes the key to understanding Marley. As Macdonald says, "a lot of people assume Bob was black and are surprised to discover he had a white father". The prejudice associated with that fact in Marley's remote home village of Nine Miles high up in the Jamaican hills helped to form the powerful quest for identity that he discovered in rastafarianism.

The contradictions of his biography were translated into a hugely seductive global metaphor for struggle and unity: "Let's get together and feel all right."

"I was doing some press with Ziggy Marley the other day," Macdonald says, "and he said of his father, 'I think Bob always regretted that he wasn't black.'

"I wouldn't put it in those bald terms, but I think that was a key to his psychology and to the music. He was always the outsider, and he found a way in his life and music to redeem that fact."

That redemption also provided Macdonald part of the answer to why Marley had huge significance not only in the Ugandan slums but among the dispossessed the world over. His film ends with a sequence of contemporary references to the singer among popular political movements. "In Tunisia at the start of the Arab spring, people are singing Get Up, Stand Up," Macdonald says. "Immediately after the fruit seller set fire to himself to start the revolution, that was the slogan written on the wall near where he died."

That influence can be measured in many ways: three decades after his death, Marley has 30 million Facebook followers.

Marley is out in cinemas from 20 April