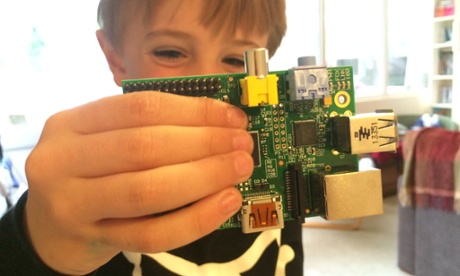

“It’s a little village!” shouts my five year-old son, waving the innards of the Kano computer in the air. “No! It’s like Lego!”

He eyes it with the expression he usually gets before pulling apart a Lego building and enthusiastically scattering its pieces around the house. We opened the Kano box two minutes ago.

I distract him with one of the enclosed sheets of stickers long enough to retrieve the motherboard, only to find my seven year-old son knocking the keyboard off the table, cracking the corner of his chair on the way.

“This is Kano. It’s a computer – and you make it yourself,” is the London-based startup’s slogan. My children appear much more likely to break the review unit that the company has supplied themselves, before it even gets made.

Still, 10 minutes later we’re sat in front of the TV, with the kit’s speaker, case and Raspberry Pi Model B computer slotted together neatly, SD card and Wi-Fi USB dongle in place, and powered on.

The stickers – intended to decorate the £99 computer – have mostly been attached to noses, foreheads, backsides and random items of furniture. But both children are fascinated by the computer’s insides. Of course they are: they’ve never seen inside a tablet, a smartphone or the all-in-one computer that I work on at home.

Much of the buzz around Kano, which raised $1.5m on crowdfunding website Kickstarter in December 2013, and started shipping its first kits out to buyers in September, focuses on what it does: programming, games, multimedia and more.

Actually, though, the device may be less important than the human relationships around it. Setting aside a couple of hours on a Saturday to make and use a computer was about time with my sons, just like a good walk, football in the park, bundling onto the sofa for a story and so on.

The technology isn’t important; the time together is. It reminds me of when I was a boy in the early 1980s, going to a Saturday-morning computer club with my dad to fiddle about with BASIC, LOGO drawing turtles and innards that may well have looked like villages. Or Lego.

Raspberry Pi is already sparking some wonderful projects that remind me of those days, and Kano is one of several projects building on it in a sensible way for parents who might be intimidated by the idea of getting a Raspberry Pi up and running from scratch.

“Hello! I’m KANO. Thanks for bringing me to life. What should I call you?” asks the computer, on-screen.

My seven year-old starts hunting and pecking keys to type in his name, before having the keyboard kicked out of his hands by his brother, who holds down the ‘k’ key for the next two minutes, then remembers that he knows how to type “BUM”.

We finally settle on a serious name, and hit the return key. An ASCII rabbit gallops across the screen, to general hysteria. Then we defuse a virtual bomb by typing “startx” within a 15-second time limit – the seven year-old manages to terrify himself by being too slow first time round, before realising it’s not a real bomb.

We log on to our home Wi-Fi network (“so that’s what the box near the front door is!”) and run a test ping to Google (“I know Google, it’s where you go when you don’t know the answer to my questions daddy”) and then wait for 15 minutes while Kano downloads a software update.

“Why are software updates so boring, daddy?” asks the seven year-old, who is learning this computing lark fast. The five year-old, meanwhile, is taking advantage of the lull to practise WWE-style splashes from the top of the sofa onto my shoulders. “I’m going to do this until the computer is ready!” he says, cheerfully.

Kano is shipping around 18,000 kits out to pre-orderers from 86 countries – around half to the US according to a recent TechCrunch report, which noted that while educational publishing firm Pearson had put in a bulk order of 500, most are going to parents.

“We are shipping the product, and it works as promised to the backers. Those were the two most important things for us,” says Kano’s co-founder Yonatan Raz-Fridman, when I visit the company’s office a few days later.

“There were 33 components, so many design, engineering and production deliverables. A lot of things could have gone wrong, and this is a young people: for a lot of them, it’s their first real startup experience. And we’ve shipped our first product as we promised.”

Kano’s Twitter account has been retweeting photos of beaming children brandishing their newly-built computers, posted by their parents. Feedback from the latter on extra features they’d like is already pouring in and being acted on.

When I visit, armed with a question about whether my children can have separate user accounts on Kano – it’s not obvious from the startup process – it turns out a tutorial is being written on exactly this point, because it’s been a common question.

A few days earlier, the software update is over, and we are exploring Pong, which is one of the preloaded modules on Kano. I’m unsure how this will go, given that my children’s previous experiences of gaming has been Minecraft, Skylanders and countless slick tablet apps. Arcade games from the 1970s... less so.

I’m surprised at how eagerly they take to fiddling about with Pong’s settings using the Kano Blocks programming language, though. The ability to change the ball’s speed, size and colour provokes near-hysteria.

“Make it brown, make it brown! GREAT BIG POO BALLS!” shouts the five year-old, as his brother fiddles with the settings. By now, Pong is unplayable because the ball is just too big, and fast. The seven year-old is roaring with laughter, and can barely type.

“NOW MAKE IT A BIG GREEN BOGEY!” I say, unable to help myself. Both children look at me, semi-scandalised. “Sorry, I was just joining in.” My wife, passing through the room, shakes her head with a look that conveys both sorrow and a complete lack of surprise.

We end up spending an hour tweaking Pong parameters, eventually with more serious intent, as the seven year-old concentrates hard on finding the correct combination of speed and ball size that will make the game playable for his brother. When he succeeds, his eyes are sparkling with pride.

Coding for kids – or programming, if you don’t like the ‘c’ word – is a controversial topic at the moment, as I’ve found when writing about it on this site.

Supporters say that encouraging children to learn programming skills and computational thinking will benefit them whatever they do later in life: less about finding the next Ada Lovelace or Mark Zuckerberg, and more about developing problem-solving and other transferable skills.

Some critics think young children would be better off spending time on other disciplines; and others argue that the way coding has been introduced into the English schools curriculum has put too much pressure on teachers who may be new to the subject themselves.

Raz-Fridman puts Kano’s view. “We’re trying to empower a new creative generation to emerge in today’s world. That involves learning to code, but it’s not just that. Some people will grow up and want to become programmers, and some won’t,” he says.

“But even those who don’t will know how to be creative with technology: how to make and play with it, in a way that can serve them in different purposes. But the fun, empowering, playful part is what comes across strongly: it’s not about coming and saying ‘today you will learn to code’.”

The important thing about the first couple of hours my sons and I spent using Kano wasn’t learning to code. It was laughing together; working together to solve some problems; one son doing something nice for the other. And yes, a new platform for GREAT BIG POO BALL fun, obviously.

None of this is specific to Kano, or even specific to technology. Parents and children don’t need a computer kit (or a tablet, or a games console) to have fun with one another.

This sounds obvious, I know, but it’s worth stating – if only as a reminder that praising a digital product isn’t mutually exclusive with seeing books, bikes, walks and any other family activity you can think of as important too.

What appeals to me about Kano is that both my children want to continue using it with me, as a thing we do together. And with modules on programming music and customising Minecraft to come, there’s plenty of fun yet to have, with a community forming around it to come up with more projects.

“This is my favourite computer,” announces the five year-old, as we turn the Kano off after our first session. “Can we make it into little pieces again? I want to play with the little village...”

• Seven kids coding projects that crowdfunded their first steps