Text, story, and the skills of writing in general, are often the games world’s poor relations. Talented games writers are frequently brought in at the last minute to work on games made without much thought having been given to character, plot or narrative. I’ve sat in meetings where commissioners have said airily that they’ll make the game and then I can “wrap a story round it”. There’s a whole school of thinking – “ludology” – that says that if an interactive experience tells a story it’s not really a game anyway. Games, it’s often thought, are sold more on their mechanics and graphics than the quality of the writing “wrapped around” them like newspaper round a fish supper. But there’s always been a niche for games that care about text; and, as a delightful new text-based game 80 Days, has raced to the top of the Apple charts, it’s a good time to celebrate them.

Some of the earliest computer games were text based: what were then called text adventures and are now known as “interactive fiction”. Games like Zork, Adventureland, and a fiendish reversioning of Douglas Adams’s Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy used “text-parsers” to tell a story and allow the player to give simple commands to move that story on. “Go north,” you’d type, and your character would go north. “Open door,” you’d say, only to be told; “The door is locked.” “Kick in door,” you might try. “I don’t understand that,” the game would tell you.

There’s still a magnificent retro charm to these guess-at-a-command-the-game-actually-understands experiences, and for those already feeling nostalgic for the words “inventory” and “examine door”, the XYZZY awards for interactive fiction have enough recommendations to keep you going through a month of rainy Sunday afternoons. But there are also newer games that keep the delights of beautifully crafted words, but offer ways to access it that are a tad less frustrating.

Emily Short’s work is always worth seeking out and exploring; she’s been a visionary in the world of text-based games for years and her personal blog is a masterclass in both reading and writing interactive fiction. I’d recommend starting with her short game, made with Liza Daly, The First Draft of the Revolution, in which your choices about how you edit letters between a husband and wife drive how the story – a sort of Dangerous Liaisons with magic – unfolds.

For a brilliantly atmospheric experience, Failbetter Games’ Fallen London is a joy. Somehow Victorian London has been stolen and fallen into hell – you navigate its strange districts and stranger people by following “storylets”. Helpfully, Failbetter has made the platform for its games, StoryNexus, available for anyone to write on. Any young person interested in writing games should be trying their hand out at making a game on a free platform like this – it’s also worth exploring Twine, Choice of Games, and the Inform 7 text-adventure-programming language, all of which offer tools to stimulate creativity and imagination in writers.

Despite all this creative flowering, text-based games are still a niche product. But I am delighted to see the success of the around-the-world game 80 Days. I detect the influence of both Short and of Fallen London in its marvellous construction, but it’s a thing all of its own, a delightful, easy-to-navigate, constantly surprising piece of interactive fiction.

The pitch is simple: you’re Passepartout. Your employer, Phileas Fogg, has taken on the bet: around the world in 80 days. You plan the route, exploring and quizzing fellow passengers. At each stopping-off point, you can visit the “market” to buy goods and if you plan carefully you’ll be able to sell them for profit later. The goal is to circumnavigate the globe and not to end up massively in debt. It is challenging enough to be engaging, but not stressful.

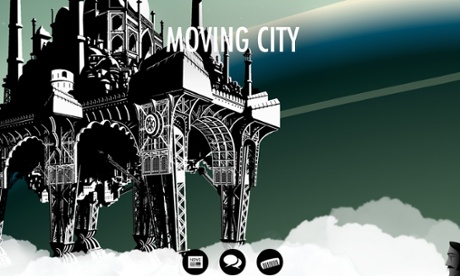

But this doesn’t begin to describe the fun and joy of the game. For one thing, the world is not exactly the earth of the 1890s. And it’s only as you do the journey that you start to understand what’s the same and what’s different. It’s sort of steampunk, but not as generic as that makes it sound. There’s a guild of artificers who make automata, everywhere from Paris to Rangoon to Stonetown to Caracas. Are the automata alive? You’ll start to wonder and to doubt, the more of the emotional, even spiritual, machines you meet on your travels.

Writer Meg Jayanth, whose previous work includes a game set in 18th-century Bengal, uses this deep narrative to comment on colonialism, but with a light and intelligent touch. And there are plenty of mini-story arcs to keep you occupied. Who did kill the engineer on your flight to Honolulu? If you don’t find out in three days, you and Fogg might be arrested for the crime. What’s behind the sadness of the pirate who plucks you from your auto-car in a drive across Europe? The fact that so many of the fascinating characters are women – easily so, without effort, as if women might just be an equal, unremarkable and not particularly sexually-focused part of the world – only adds to the deep satisfaction of this game.

The design experience of playing 80 Days is extremely pleasing, with enough visual flair and audio effects to be immersive. The storytelling is fluid, and manages that rare miracle of being interactive enough that you feel you’ve influenced events, without collapsing the narrative completely. And, as a game about adventure, even set in a world of jewel-eyed automata and giant birds, it really captures the joy of travel. In fact, I suspect that this game is half responsible for my now planning a trip to Delhi and maybe one around the world.