The hero of Michael Winterbottom's latest film is a director called Thomas, played by Daniel Brühl. A former enfant terrible whose graduation to Hollywood ended up a flop, he has come to Siena to research a new project and try to rekindle his career. The longer he spends in this medieval Italian city, however, the more troubled he becomes, and soon his sleep is haunted by visions. Again and again he finds himself standing alone against the old walls, stalked by murderers, assailed by flying serpents, confronted by the laughing face of his ex-wife. It's as if he were Jack Nicholson, in a Tuscan version of The Shining.

The dream sequences pepper the middle act of The Face of an Angel. They're bewildering, involving and entirely disconcerting. They also have almost nothing to do with the ostensible premise of this film. What begins as a fictionalised account of the investigation into the murder of a young English student, by an hour in, becomes a journey through the psyche of a washed-up film director.

Winterbottom is no stranger to picaresque story-telling – he dramatised Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy. Nor is he unfamiliar with the metanarrative: his Shandy was actually about two actors trying to adapt the unfilmable book. But when the subject matter – though names have been changed – is the killing of Meredith Kercher and the prosecution of her housemate Amanda Knox, such film-making techniques carry risks; of seeming high-handed perhaps, or of missing the point.

The questions that this film actually asks is: why were people – British, American, Italian – so obsessed with this murder? And why did this obsession come at the expense of empathy for the Kerchers? At the heart of any response is that the media were to blame.

In the opening scene Thomas meets an American journalist, Simone (Kate Beckinsale), whom he hopes will give him access to the truth of the case. She in turn introduces Thomas to the Siena hack pack, a gaggle of stringers whose every waking moment is spent thinking about the case, apart from the moments when they're necking espresso in the local cafe. There's a British tabloid man, an Italian crime correspondent, an American grande dame, all of them witty, knowledgeable and willing to do whatever to get a story and then laugh about it afterwards.

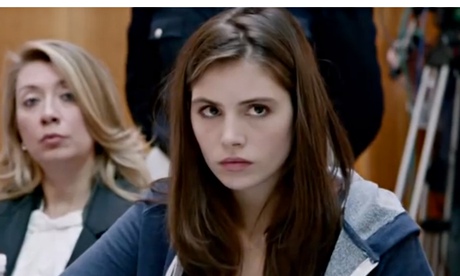

The other characters Winterbottom introduces us to include slumlord and local eccentric Edoardo and another English student, Melanie. Played by the model Cara Delevingne in a striking debut performance, she is the spirited counterpoint to the journalists' cynicism and as such is Thomas's route to salvation (there's another Dante parallel in there). But as we become more involved in the relations between these characters, there's still the nagging question at the back of the mind: yes, but what about the crime?

The Face of an Angel wants its audience to think more about what really matters: love and the memory of those who have been lost. But it makes assumptions in doing so. Who's to say, after all, that the public weren't empathising with the Kerchers at the same time as wondering whodunnit? And while criticism for the hacks and their practises may seem fair (although the film acknowledges that without them, some evidence would never have come to light), it never really explores the question of why people are fascinated by sex and death. Such behaviour may be prurient, but is it not also natural?

There are lots of things to recommend about this film. The hack-pack scenes are riotous and witty, while the deadpan observation of the workings of the film industry feels just depressing enough. The cinematography of a largely gloomy Tuscany is breathtaking. But every compelling moment feels like a deliberate distraction from what everyone – on screen and in the auditorium – is thinking.

• Full coverage of the Toronto film festival