The appeal of Fiddler on the Roof is paradoxical – it’s a celebratory musical about loss. The show opened on Broadway on 22 September 1964, and is still revived 50 years on. Why did it succeed then, and why does it still hold audiences?

Fiddler is a history musical, set in 1905 in a tiny Russian village called Anatevka (“underfed, overworked Anatevka”). Tevye the milkman and his wife Golde are scraping a living and raising a family in a state where indifference turns to hostility. His story is told in book, music and lyrics by, respectively, Joseph Stein, Jerry Bock and Sheldon Harnick. They were badgered by Jerome Robbins, the show’s director, to define its emotional core, eventually replying “it’s about the dissolution of a way of life”. On a domestic level, Tevye’s daughters sidestep tradition, choosing husbands despite barriers of income, politics and religion. The entire Jewish community moves on in the wake of tsarist persecution – Anatevka’s fate figuring the upheavals across eastern Europe and the devastation of the shoah.

Fiddler hasn’t just taken its place in postwar American Jewish identity – as Alisa Solomon’s recent cultural history suggests, there’s a strong argument to be made that it was central in the formation of that identity. After decades of cautious assimilation and the trauma of the Holocaust, by the mid-1960s American Jews felt more secure in their nation’s civic and cultural life. It was time to revisit their roots – speaking through entertainment to both their own community and to a wider culture.

This didn’t mean that Bock’s melodic weave sounded especially radical. Winding, minor-key melancholy and hectic fervour had long characterised Broadway scores, but when Irving Berlin or the Gershwins had evoked a longing for home, a needling nostalgia, they often located it in America’s deep south. Whatever the story, Jerome Kern averred, he could cloak it in “good Jewish music”. The songwriters had both emerged from close-knit Jewish families: Bock’s elderly grandmother sang “childlike words and music” to him in a “fragile Yiddish voice”. In Fiddler, he reclaims the Broadway idiom’s ethnicity; the violinist’s yearning melody, playing as the villagers trudge away from Anatevka, is a seed of the American musical. “I never felt the urge to research the score,” he claimed, “I felt it was inside me.”

Yiddish had been the lingua franca of eastern European Jews settling in New York, producing a thriving culture of theatre, print and comedy (Molly Picon, star of Yiddish theatre, would play Yente the matchmaker in the film of Fiddler). But education and assimilation diminished its cultural currency. Harnick had seen Yiddish jokes in Lenny Bruce’s act fall flat, and in his musical confined the language to song titles such as Mazel Tov and Lechaim. Jewish audiences might want to revisit the shtetl, but not to move back permanently, so Fiddler celebrates Yiddishkeit without the Yiddish – both honouring the community’s origins while marking its distance from them.

No director was better suited to this material than Jerome Robbins – an inspired director and choreographer (On the Town, West Side Story) for whom identity was all conflict. He was as uncomfortable in his ethnicity as in his sexuality or political activity (he’d named names at the HUAC hearings, claiming he was threatened with exposure of his homosexuality).

Working on Fiddler connected Robbins with his Jewishness; he wanted, he said, to “give another 25 years of life to that shtetl culture which had been devastated during world war two.” The virtuoso antics he witnessed when smuggled into a Hasidic wedding inspired the exuberant bottle dance in the first-act finale, and his choreography is now considered as integral to this show as it is to West Side Story – as David Leveaux discovered when seeking to discard it for his 2004 Broadway revival.

Steeped in Marc Chagall’s fantastical paintings of the shtetl, Robbins suggested adding his characteristic fiddler on the roof to the show. The artist was also his first choice as designer, but he declined, and disliked his work being associated with the show. Instead, the pioneering designer Boris Aronson, whose father was grand rabbi of Kiev, channelled Chagall’s pastels on stage (the film created a dark sepia patina by stretching brown hosiery over the camera lens, reinforcing the sense of a sombre past).

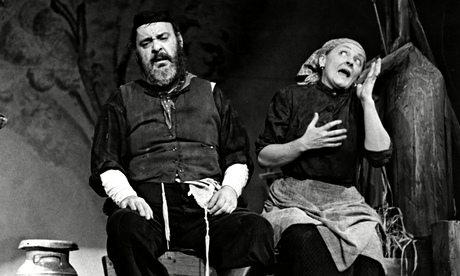

Tevye is central to the show’s charm, monologuing at the almighty. Stars including Frank Sinatra, Danny Kaye and Walter Matthau were considered – or suggested themselves – for Tevye, but Zero Mostel (Max Bialystock in The Producers) assumed the role into his outsize stage presence. He captured both Tevye’s mischief and shadows, though over the long run his fidelity to the script waned. “Listen,” he told the unhappy writer, “when I’m on stage, it’s between me and the audience. Everybody else has to get outta the way.”

Fiddler continues to reward a star turn set in a strong ensemble: Chaim Topol premiered the role in London in 1967, played it on film and was still reprising it in 2007; his successors include Harvey Fierstein, Henry Goodman and Paul Michael (“Starsky”) Glaser, who as a young actor had appeared in the film. If there’s a reason for the show’s widespread appeal, it may be the satisfying tonal spread: its schmaltz is cut by cruelty, its melancholy arc stippled with indomitable merriment. Anatevka is wiped from the map, and that erasure – faced with spirit and fear – casts a shadow that can still feel familiar.