Polymath musician, writer and scourge/darling of the music press, Nick Cave has played a number of intriguing screen roles over the years. In John Hillcoat’s Ghosts… of the Civil Dead he was a psychotic inmate in a high-security prison descending into hellish self-destructive chaos. In Tom DiCillo’s Johnny Suede he played Freak Storm, a parodic rocker with a shock-white quiff singing songs about his daddy dying in the electric chair. Most notably he was a balladeer in Andrew Dominik’s brilliant (but underrated) The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, infuriating Casey Affleck’s hollow gunman with his inaccurate musical recounting of already legendary history.

Now, in the fictionalised documentary 20,000 Days on Earth, Cave plays a mid-50s rock icon living in Brighton, working on his writing, attempting to make sense of his own quasi-mythical existence. The film may be nominally factual, and the character he plays may share Nick Cave’s name, but this is as much of a performance as any of his previous screen roles.

While rocker-docs invariably promise to lift the veil of stardom, viewers of titles as diverse as Don’t Look Back or In Bed With Madonna will know that the genre generally reinforces, rather than deconstructs, the public personae with which we have become infatuated. Indeed, it’s arguable that fiction films such as Donald Cammell and Nic Roeg’s Performance (to which this owes a debt) or Roeg’s The Man Who Fell to Earth brought us closer to understanding the mystique of Mick Jagger and David Bowie than the numerous “documentaries” that have struggled to disentangle fact from fiction.

20,000 Days on Earth ostensibly take stock of Bad Seed Cave’s life as he passes the titular age milestone. The format is self-consciously “intimate”: a day in the life of Cave, starting with his theatrical awakening in bed and progressing through a therapy session, a recording session, staged family time with the kids, a live concert and scattered personal encounters. Some of these take the form of in-car conversations, Cave prowling the streets in his retro Jag with the likes of Ray Winstone (who starred in the Cave-scripted western The Proposition) and Kylie Minogue (with whom he recorded the murder ballad Where the Wild Roses Grow), the windscreen providing a mobile proscenium arch.

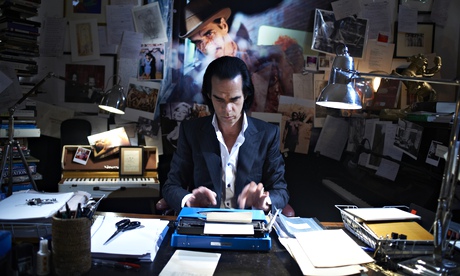

Less of a biography than a widescreen installation with script and music (Cave’s co-writing credit confirms the artifice), this flits between handsome neo-noir pastiche and ripe psychological melodrama. Cave is in costume throughout, wardrobed in louche suit, Vegas shades and post-Birthday Party hair, delivering hard-boiled, pre-scripted voiceovers and “off the cuff” observations about the artistic process in the same well-rehearsed deadpan drawl. Even when unburdening his soul to psychoanalyst Darian Leader (his first sexual encounters, the death of his father), the tone is one of arch self-regard, a man who has created a stage persona talking about himself in character. Later we see him sharing a meal with long-time collaborator Warren Ellis, playing the part of a man eating food with a beardy close friend and companion, and playing it to a tee.

None of which is to suggest that the film is dishonest, merely that it is an act, in the same way that Casey Affleck’s portrait of Joaquin Phoenix in I’m Still Here was all for show. Even the location is a construct: Cave drives around, and talks lovingly about, Brighton, but the footage leaps unannounced across temporal and spatial boundaries, the film-makers playfully conspiring to blur several worlds into one artificial reality.

Sometimes you’re unsure whether to laugh, scream or yawn as Cave (who retained final cut) sifts respectfully through the landscape of his own legacy. Scenes of him browsing his visual archive and poring over his writings evoke the spectre of the vanity project. Yet anyone whose last will and testament demanded the establishment of a Nick Cave Memorial Museum clearly has a sharp sense of humour, and Forsyth and Pollard (who have worked with Cave before on projects such as short film series Do You Love Me Like I Love You) are as wry, dry and entertaining as their subject.

As much as this is a film about Cave, it is also a cinematic portrait of Brighton or, more precisely, the idea of Brighton. More than once I was reminded of Toby Amies’s terrific documentary The Man Whose Mind Exploded, an affectionately fractured account of amnesiac Brighton legend Drako Zarhazar who decorated his tiny apartment with fragments of his multiple lives: photographs, ornaments and enigmatic messages plastered on walls, splayed across floors, hanging from ceilings.

Cave, meanwhile, describes creating an alternative and, crucially, coherent universe within his music, novels and screenplays into which he ventures every time he writes and records. It is a rich Old Testamenty world in which the forces of good and evil are constantly at war – the stuff of myth rather than day-to-day reality. Cave may not believe in God or the devil, but his art most certainly does – in much the same way that this fascinatingly self-obsessed film believes in Cave.