If there's anything guaranteed to mark you out as a hopeless geek, it's surely an interest in role-playing games. They are a perfect storm of all the "non-manly" things, a combination of "female" imagination and childish let's-pretend play with the too-clever-by-half, maths-based dice-rolling and the vague sense that games really should involve men sliding around in mud and grabbing other men's taut, muscular thighs. Not to mention that role-playing games are co-operative rather than competitive and there's never really a winner. Just imagine if that were an ethos we taught our children. I shudder to think.

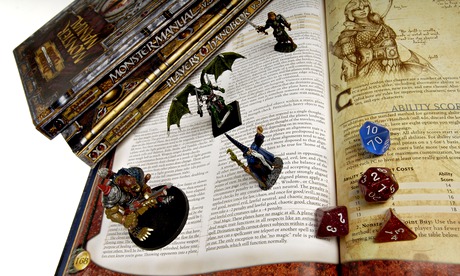

Let's put aside our fear of being considered not macho enough and celebrate the fifth edition of the classic tabletop role-playing game Dungeons and Dragons, which launches this year. You don't have to be intending to settle down with 20-sided dice (D20s, to get technical) to be interested in how role-playing games work. You don't even have to ever play one to learn a lot about character development from them. They might even hold the key to solving some of the greatest technological challenges of our time.

Dungeons and Dragons, first published in 1974, is the old and venerable grandaddy of a format that once looked as if it might vanish, but has been revived. This is how it works: you and a bunch of friends sit around a table. You each create a "character" by rolling dice to determine basic skills and attributes such as strength, agility, intelligence, even wealth, beauty or charm. You give your character a name. You have a think about what their characteristics might suggest about their personality.

Then one person – the dungeon master – explains what kind of adventure your characters will go on. You might be going to steal something, to investigate mysterious lights in the caves, to protect a cartload of valuables through a thief-infested forest, or any scenario you've ever seen on TV or in a movie or read in a book. You tell the games master what your character is doing. You might get into a fight and have to roll dice to decide whether you've dealt a killing blow or dropped your sword on your toe. The adventure won't go the way you thought. There'll be story twists, and battles will go wrong, and you'll have to make clever split-second decisions to bring your character (to whom, by this time, you'll be quite attached) safely home. This stuff has constituted some of the most fun evenings in my life.

What role-playing games do so beautifully is to provide a structure for non-writers, people who might say they're not very imaginative, to create characters. Those dice rolls, those bare-bones statistics – like the two dots and a line that suggest a face – start to encourage anyone to imagine a character. If this woman has come out through some random number generation to be physically agile, not very attractive, but skilled at thievery, how did she end up working in this library?If this man's got a lot of money, is quite bright, but is only averagely strong and catastrophically clumsy, what's he doing on an Arctic expedition? So much of storytelling is in the gaps, in allowing the imagination to work.

Tabletop role-playing games translated seamlessly to video almost as soon as they were devised.Microprocessors could deal easily with the maths of deciding who had won a battle and how many hands they had chopped off. The dnd videogame appeared in 1975. Ian Livingstone – who with Steve Jackson wrote the role-playing games-with-training-wheels Fighting Fantasy Gamebooks, some of which I knew almost by heart as a child – later founded Eidos, creators of, among other things, Tomb Raider. Since the 1970s, role-playing games have been among the top-selling videogame genres, including the wildly popular Diablo II (to which I lost four months of my life in 2001-02), and the online mega-hit World of Warcraft.

The stickiness of these games has been much discussed – and there's certainly something tremendously satisfying about the constant progress. Every time your character uses a skill, her or his stats in it increase. Unlike in real life, everything that you do, whether it succeeds or fails, improves you, and things are always getting better. I've heard role-playing games summarised as "get better trousers" games – and there's a bit of that too, an acquisitive lust for imaginary objects to improve your character. This side of things is well-parodied in the online comedy game Kingdom of Loathing. But you feel affection for the unique character you've developed – not much different to the affection I feel for my own cackhanded attempts at pottery: I love them because they're mine.

Generating a character through simple algorithms and then trying to make it rounded and real enough to generate emotions is one of the big challenges in modern computing. It's the quest for artificial intelligence. Or at least the quest for something that might be artificially intelligent enough to pass the Turing test. How do humans behave, how do they come to seem real to us, what character developments are realistic and which are out of place? Role-playing games, novels, psychology and work on artificial intelligence are all trying to answer questions in this area.

And that's the thing; though individual characters might be wooden, something feels real about these number-based systems for generating workable models of human beings. Perhaps it is the spread of humans you get if you keep on rolling up characters. Some have brains but no charm; some the looks but not the money. Some lucky bastards get a row of high scores. Some poor sods get nothing much in any category. And then you try to do the best with the character you've got. Role-playing games might not yet be creating imaginary characters you could confuse with real people, but they've got the fundamental unfairness of human life nailed.