Dating service OkCupid has cheerfully admitted to manipulating what it shows users, a month after Facebook faced a storm of protest when it revealed that it had conducted psychological experiments.

Christian Rudder, OkCupid’s co-founder and data scientist, posted three examples of experiments the firm had performed on to the site’s OkTrends blog, in an upbeat article entitled “We Experiment On Human Beings!”.

The blog, which used to chronicle the discoveries OkCupid made by observing its users’ behaviour, has been mothballed for three years, since OkCupid was purchased by dating behemoth Match.com in February 2011.

“OkCupid doesn’t really know what it’s doing,” writes Rudder in the most recent blogpost. “Neither does any other website. It’s not like people have been building these things for very long, or you can go look up a blueprint or something. Most ideas are bad. Even good ideas could be better. Experiments are how you sort all this out.”

Rudder refers specifically to Facebook’s troubles over its experimentation, when the firm tweaked the content of users’ news feeds in an effort to discover what their reaction was to a higher proportion of positive or negative posts. “Guess what, everybody,” he says, “if you use the internet, you’re the subject of hundreds of experiments at any given time, on every site. That’s how websites work.”

The first experiment Rudder describes occurred in January 2013. To promote the site’s new blind date app, OkCupid removed all pictures from the site, calling it “Love is Blind Day”; sure enough, fewer users were active on the site, but of those who were, first messages were responded to 44% more often.

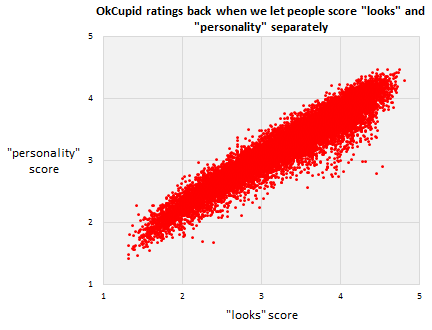

The second involved attempting to discover how much of a given user’s rating – the score ascribed to them by other users – was derived just from their picture. By presenting a small subset of users with their profile text hidden, Rudder found that just 10% of the typical user’s score is based on the text they write on their profile. The vast majority of the rating, it seems, is based purely on the picture.

The final experiment Rudder describes has proved more controversial, however. OkCupid assigns users a “match” rating, showing how likely it thinks a pairing is to get along. The rating typically proves accurate, but, Rudder writes, “in the back of our minds, there’s always been the possibility: maybe it works just because we tell people it does. Maybe people just like each other because they think they’re supposed to? Like how Jay-Z still sells albums?”

To test its theory, the site lied to a portion of users about how strongly they matched with other users, and observed how many single messages led to a full conversation. Sure enough, they found that two users who actually had a 90% match but were told that they had a 30% match were less likely to carry on talking than two users who actually had a 30% match but were told they had a 90% match. In other words, Rudder says, “if you have to choose only one or the other, the mere myth of compatibility works just as well as the truth.”

But while OkCupid’s blog post was seemingly an effort to demystify the process of experimenting on users, for many, it simply underscored the tech industry’s failure to “understand why some testing is ethical and some is not”, in the words of the sociologist Nathan Jurgenson. Despite OkCupid’s personable demeanour, the firm is owned by the IAC conglomerate, a multinational corporation with a market cap of $5bn. “Tech folks routinely equate emotional manipulation and a logo change,” Jurgenson continued. “[You] need an ethics board to distinguish what requires opt-in, debriefing, etc.”

At one end of the spectrum lie Google’s famous A/B tests, where the company experiments on users to find out which shade of blue is most effective for outgoing links, while at the other lie Facebook’s experiments on users. The question posed to tech firms is whether there’s a line which is crossed, and where that line is.

For others, though, even the most basic experiments still pose awkward questions. Academic Zeynep Tufekci points out that 62% of users are “unaware even of the existence of Facebook newsfeed algorithms.”

For her, “OkCupid’s finding people talked more when falsely told the algorithm ‘matched’ them highlights the stealth power of algorithmic mediation.”