At the end of Tina Renton's book, You Can't Hide, she thanks her friend Richard John Taylor for everything he's done for her. Taylor, a film-maker, had become a saviour of sorts. He had met her through Rape Crisis in August 2011 when she was at her most vulnerable, befriended her, gave her a job as his personal assistant and made her feel worthwhile again.

Renton's story was as inspirational as it was shocking. She had been abused by her stepfather from the age of six. At 14, she told her mother, but her mother said if she went to the police, the family would be left homeless. She threw her partner out of the house, but he returned within two days. Renton left home, had two children, when she was 19 and 20, split up from the father when they were one and two, and brought them up as best she could.

When her eldest son was excluded from school at 10, Renton appealed. She represented herself, won the case, and a man from the local authority asked if she'd ever considered being a lawyer. Of course she hadn't – she'd left school with no qualifications. But she started to think about it. She did an access course at college, studied law and graduated with a 2:1 in 2009. In her final year, she was studying the Sexual Offences Act and discovered that there is no statute of limitations in Britain. A light went on: 29 years after she was first abused by her stepfather, she reported him to the police. In July 2011, David Moore was sentenced to 14 years in prison at Southend crown court.

Renton gave evidence behind a screen, but then decided to go public. If she waived her right to anonymity and told her story, it might encourage others to come forward. She was interviewed by the Basildon Echo in July 2011 and the story was picked up by the national press. Renton was portrayed in the Daily Mail as a popular hero – the brave victim who brought her monstrous stepfather to justice. She soon had an agent and a book deal, which was when Richard John Taylor came into the picture.

Taylor contacted Rape Crisis, who put him in touch with Renton's agent. He said he was making a documentary about rape and sexual abuse, to be called I Want To Talk About It. He told Renton why. "He said he'd been out with a young lady and had been set upon by four people – one of them a girl. His girlfriend was raped in front of him, and he was beaten up."

It made sense to Renton that a film-maker who had experienced such horror would want to document it. She told him she'd be happy to take part. As well as Renton's story, the film featured Crissy Rock, who had starred in the Ken Loach film Ladybird Ladybird, and told how her eldest child was the product of rape. Another woman, whose face was covered, talked of being gang-raped at 19.

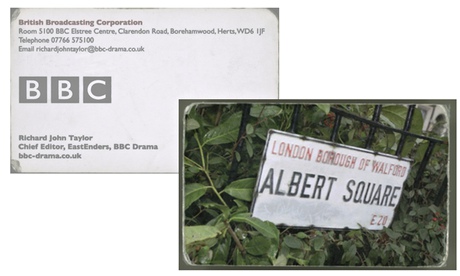

Taylor had an air about him; the 27-year-old had a confidence Renton liked. "He was quite hard to talk to when you first met him," she says. "But the way he dressed, there was something about him, as if he had power and knowledge and money." She was invited to his apartment, which was decorated with photographs of Taylor with celebrities – Simon Cowell, Adele, Spandau Ballet singer and EastEnders actor Martin Kemp, and the actor Billy Murray, who had played gangster Johnny Allen in EastEnders. She was impressed, but it made sense that Taylor had all these EastEnders friends – after all, he told her, he was chief editor on the BBC soap opera. He wasn't a boastful type, but he had given Renton his card – a photograph of the classic Albert Square sign in the fictional London borough of Walford E20 on one side, British Broadcasting Corporation in an impressive bold red on the flip side. The address was Room 5100, BBC Elstree Centre. Email richardjohntaylor@bbc-drama.co.uk.

Renton couldn't afford the one-year legal practice course, the final stage in qualifying as a solicitor. But she did go to work for Taylor. "He asked me to be his personal assistant at his company Princess Films. And I was like, are you serious? There was never a romantic connection, but I felt he was my best friend. Because of my past, I don't trust anybody. But I trusted him, to the point where we'd even had a conversation about making him an executor of my will in the event that I die, so my children were looked after."

Taylor went on to write, direct and edit Acceptance, a revenge thriller about rape, "inspired by true events", starring Crissy Rock, Leslie Grantham, Billy Murray and Chris Langham. Taylor told Renton he had substantial backing from ITV to make Acceptance. In its closing credits, she is listed as third assistant director. They spent a great deal of time together – in bars, at dinner parties; they even went on a recce to Bulgaria for the next film Taylor hoped to make, provisionally called The Factory. He told her he had acquired the rights to the Roald Dahl classic Charlie And The Chocolate Factory and was going to make a new version.

Renton, now 38, had come into some money – the advance for her book and compensation for a holiday disaster. She thought of investing it in Taylor's company, but he told her he didn't need her money. Later that day, he approached her with an idea. "He told me he had a Turkish bank account and an apartment in Turkey, and he could put money in there. If he had over a certain amount, which I was led to believe was more than £1m, he'd get a good interest rate on it. He said if I invested, he would give me the 18% interest it gained a month." A month? She nods. "So I gave him £3,000 in cash and my agent transferred £5,000 straight from my account. So on the £8,000, it's £1,400 a month."

Meanwhile, Renton had completed her book. She gave it a final read and wrote in her personal thank you to Taylor. "He's the only one because I felt he'd done so much for me. Then, from the day I sent it to be printed, he started being funny with me. He didn't want me to come down to work, didn't want me to see him, he started being shitty and short in his text messages. Something wasn't right."

Niall Long (not his real name) met Taylor in July 2012 through his daughter, an aspiring actor. Long is a successful London businessman in his 50s, who works with major Hollywood studios. "My daughter got a small part in one of Taylor's films, and said, 'Daddy, I think he's got a few quid, he lives in a lovely big flat, he works for the BBC.' She said he was looking for an investment. I said, 'OK, I'll have a meeting with him.' I'm always interested in something where I can make some money."

Taylor was dating Long's daughter, and they were soon engaged. Taylor showed his prospective father-in-law the glossy brochure for a film adaptation of the TV detective series Hazell, and Long was impressed. "So I took that away and thought, OK, for £50,000, I'll take 25% of the film, and we drew up the contract. Then it turned out it wasn't going to be Hazell any more. He fell out with the original series actor Nicholas Ball. He said, it's now going to be another film, called Acceptance, starring Billy Murray and Leslie Grantham. At that point I was given the choice to pull out, but he assured me – and I've got it in writing – that ITV were still on board and had guaranteed it to a minimum of £420,000. During filming he needed more money because one of the investors dropped out, so I gave him a personal loan of £45,000." Long was told that as soon as the ITV money started coming in, the investors would be minting it.

Robin Stone (not his real name), a retired building project manager, met Taylor in September 2011 at a bar in London's Docklands. "I was just sitting there one night, chatting with the owners, and he walked in and introduced himself. They said they knew him. He then told me he was part of the BBC, an editor, gave me a card, explained his situation with regards to him having been beaten up and his girlfriend raped." Stone pauses. "Considering I'd just met the guy, I managed to find out a lot very, very quickly. But essentially he was looking to get money together to do this rape documentary."

A few weeks later, Taylor invited Stone to a screening of I Want To Talk About It, and talked to him about his passion for film-making. He told Stone he had funded the film by undertaking a sponsored swim across the Channel in 18 hours. (A JustGiving page shows that more than two years since Taylor started collecting funds in the name of Rape Crisis, he has raised £563, or 11% of his target of £5,000.) Stone had himself done charity runs for Children In Need, and was interested in supporting another good cause.

"When I first met him," Stone says, "he came across as charming, ambitious and caring, in so far as he wanted to right wrongs. Four days into the shoot of a new film, Fifteen, he threw out this bombshell that he might not be able to finish it because he was short to the order of £5,000. It was only a small amount, and you put the money in thinking something may or may not come out of it."

Stone began to get the investor's buzz. After all, Taylor was a man with contacts, and he was apparently getting the work done. Stone invested £35,000 in Acceptance. "I hadn't invested like this before," he says. "It was because I thought I was seeing an end product, and I believed he worked for the BBC."

Taylor's next project was a documentary he hoped would help clear the name of the actor Chris Langham, with whom he had worked on Acceptance and who had been convicted in 2007 of downloading child abuse images. He claimed Langham had been smeared by the British press, which had labelled him a paedophile. Taylor showed Stone an impressive brochure for his production company, Taylor Theroux Limited. On one page was a photograph of the documentary-maker Louis Theroux and a mini CV. Underneath was a photograph of Taylor and a potted biography: "An editor of award-winning films and television, Richard set up Princess Films in 2010 with the aim of producing engaging, unembellished, and thought-provoking feature documentaries. His directorial debut was the hard-hitting documentary I Want To Talk About It, investigating the devastating realities of rape, which will be aired on More 4 in early 2012."

Taylor told potential investors that Langham had been unfairly maligned. The brochure gave prominent space to the stars who would appear in the film to defend him, including Steve Coogan and Hugh Grant, who had both campaigned against press intrusion into privacy.

Stone said it was this brochure more than anything that convinced him to put money into the project. "I invested £10,000 based on all the information he'd given me. I have to admit, as soon as he mentioned being in business with Louis Theroux, I was impressed." The £50,000 Stone invested in total was his pension money, and he was confident it would reap its reward. It had to – this was the money he had put aside in case his mother, who had multiple sclerosis, had to go into a home.

"I took an early pension, so I can survive month to month, but it was money I wanted to use for other things." Like Renton, Stone was happy to put the money in Taylor's Turkish bank account after the film-maker showed him there was already £1m in there.

Taylor had told Tina Renton not to worry about her book launch; he was going to look after all that. The party would be held at one of several apartments he owned in Docklands. That's how he had made his money, he told her – buying and selling property. Although Taylor paid her only for the hours she worked, Renton had begun to take his ironing home as a favour. But the more she did for him, the more strangely he behaved. "He said if I was working for him, I should always be there for him, that he should be able to click his fingers and I'd be there." Just before Christmas 2012, she was having her nails done when Taylor rang. "He said, 'Can you come over?' I said, 'Not now, I'm having my nails done' and he got right shitty with me. I dropped his ironing off on New Year's Eve and he sent me a message saying I should have tidied up and put his rubbish out, and I thought, 'Nah, not having that, I'm not hired as a cleaner. I did that as a favour.' New Year's Day I woke up to another barrage of abuse from him on text message and I decided I'd had enough. I said, 'I'll do the book launch myself, thanks very much.' He still owed me three months' interest on the bank account, and I'd lent him some money as well. The grand total, including the interest, was nearly £14,000."

Renton stopped working for Taylor and started to chase her money. "It was always, 'Next week, next week, next week…'" She made inquiries, starting with EastEnders. "When he stopped paying me, my gut told me I needed to start poking around. So I phoned EastEnders and said, 'Can I speak to the secretary of Richard John Taylor, chief editor?' and I found out that not only was he not chief editor, but he'd never done any editing at EastEnders. The only thing he'd done at the BBC was work as a runner for a few weeks way back when."

Renton met with an investigations team at the BBC, who told her that his EastEnders pictures on Facebook were false, that his EastEnders business card was fake, that Room 5100 did not exist and that Taylor's email was not a BBC address. She discovered that the properties he claimed to own did not belong to him, and that ITV had never heard of a film called Acceptance, never mind commissioned it. "I have dug into this man's life," Renton tells me. "I know more about this man than he probably knows about himself. He owes so many people money, not just me."

She has reported Taylor to the police, but she doesn't believe they are investigating him seriously. "The police officer came to take a basic statement. They didn't seem that interested."

The Metropolitan police confirmed that complaints from Renton and the BBC about Taylor had not been taken further. A statement said: "The incident was resolved in a civil dispute. No persons have been arrested. Words of advice were given to both parties."

When we first spoke last May, Renton was in desperate trouble. "I applied for a county court judgment and a friend lent me the money. He'd put me in a situation where I could actually lose my home, because I can't pay my rent. The money I got from my book was an income, an earning. I can't sign on. My rent is £850 a month. I've got six weeks, then I've got to get out. I'm two months behind with my rent."

Last year, Taylor told her he was withdrawing money from the Turkish bank account. "He said he would pay me by cheque, which he insisted I go and collect from his apartment, and then he stopped the cheque. I knew he was never going to pay me."

In autumn 2013, Renton contacted me to say she had still not received any of her money from Taylor. I didn't hear from her again until this January, when she said she'd like to meet me with Long and Stone, who had both been in touch with her. Their paths had crossed before, because of Taylor, and they'd all decided enough was enough.

Long is a small, imposing man with a high-pitched voice and the look of Joe Pesci. Stone is quietly spoken and retiring. When we meet, they agree to be interviewed on the record, but later ask to have their names changed because they fear their association with Taylor could be professionally damaging.

Long can take the financial hit, but he's angry – angry that Taylor has messed with him and his daughter (the engagement was called off after two months, when she discovered he was seeing other women). This is the first time Renton, Long and Stone have met to talk about their money. Taylor had sowed seeds of distrust, so that they became suspicious of each other. But today they are united – in their desire to get their money back, and to stop others from being conned. At times, they seem unsure whether to laugh, cry or form a vigilante group.

"He's an extremely convincing conman," Long says. "That is the word. But once one begins to see through that, you then go back and see everything. Even on the film Acceptance, there were two producers' agreements. I've got one, 50 grand for 25%. Robin's got one, 35 grand for 38%. He was very good at playing one of us off against the other."

In one way or another, rape is addressed in Fifteen and Acceptance, as well as in the documentary. But what disturbs Renton is the manner in which it was approached – the main character in Fifteen, who happens to be a film editor and looks similar to Taylor, sleeps with his underage sister. Ultimately, it is the sister who is blamed for leading him on. Like all Taylor's other films, Fifteen never gained a distribution deal. Louis Theroux is thanked in the final credits.

Does Stone think Taylor is serious about his film career? "He did want to be a film-maker, but he wanted to do it in a very rapid way without involving other people to tell him how to do the filming. And while he did use the money for the films, I also think he used it to subsidise his lifestyle. He told us the films cost far more to make than they did."

I ask the three investors what they think of the films.

"Acceptance isn't bad for the money we put into it," Stone says.

"Let's be really honest," Long says, "it was crap. I saw it in LA, when he showed it to Americans, and we had three people fall asleep. When I came out, idiot that I was, I said to one fella, 'What d'you think of the film? I produced it' and the fella said, 'I don't want to hurt your feelings.' And I said, 'No, come on, it's not my film, I just put money into it.' And he said, 'It's one of the worst three films I've ever seen.' So there you go."

None of the films, which were made cheaply and very fast, has ever been broadcast. Channel 4 said of I Want To Talk About It: "We have checked all records and have no record of this film being broadcast or being commissioned for More 4 or any of our channels."

When Taylor's investors talk about the various ways in which they were gulled, they verge on the competitive.

"He told me that Letitia Dean, who was in EastEnders, will only let him edit her work," Long says. "I introduced him to people in LA who no longer want to talk to me because he's crossed them as well."

"He's told us he owns all of these flats round West India Quay, but they are all rented," Stone says. "Then, around two weeks before Christmas, he promised me my £10,000 from the documentary and told me he had ordered a cheque. I spent the whole week, day after day, arranging to meet him in Canary Wharf. And he didn't turn up. Then I accidentally met up with him in this bar, and I said nothing to him because, quite frankly, I would have hit him."

Renton and Stone say Taylor doesn't return their calls. "He knows I don't have the financial clout to follow things through," Stone says. "He also knows I know it's pointless doing anything like a CCJ [county court judgment], because he just collects them for fun."

Long says Taylor does return his calls because he's scared of him. Why? "He knows I've got the money to do what I need to do. Yes, I do know the right people as well." The astonishing thing, Long says, is that despite the betrayals, Taylor still acts as if he has a good relationship with him. "He was meeting investors for a new film and said, 'Can you come and big me up a bit and say what a good deal you got out of Acceptance?' Can you believe the cheek?" His voice rises a notch higher, and he looks at the others. "I said, 'Do you believe I'm some kind of...' I said: 'a) I've got nothing good to say about you; and b) if you think I'm going to allow you to do this to some other poor bastard, you've got another think coming.'"

Why have Long and Stone not been to the police? They look embarrassed. Perhaps they don't want to admit how naive they've been. Well, the thing is, they say, Taylor has paid them bits back – Long has had £20,000 of his £95,000 back; Stone has had a £10,000 loan returned, but not the £50,000. Renton insists she has received none of her £13,900.

"I've been really busy," Long says. "I know that sounds stupid."

"The other thing with regards to the police," Stone says, "is part of me thought, where would I stand with that, given Tina's situation? She has already contacted the police, and they seem to be getting nowhere."

The funny thing is, Long says, barely a week goes by without Taylor promising him or his daughter he'll return the money. "Yesterday my daughter got a text saying, 'I've never lied to you or your family.'" He shows me the text.

As we are talking, he receives another text from Taylor. "It says, 'I'm still chasing your money.' This is a response to a text I sent him last week." Who is he chasing? "Some other poor bugger he's trying to get money from."

In February, I hear from Renton that Taylor is now running a restaurant in central London. She says he is registered as its director at Companies House and wonders where he got the money from. By now, I feel as if I know Taylor well. But I have never met him, and it is time to put Renton, Long and Stone's allegations to him.

A few weeks later, I turn up unannounced at the restaurant with a photographer. It is small, fairly smart and serves French cuisine. The walls are covered with framed photographs of movie stars, or people who look like movie stars. Taylor is standing with one arm propped against the bar. He is tall, dressed entirely in black, with snakeskin boots and a ponytail.

He agrees to talk, first without a tape recorder, promising that he will then repeat his story on the record. He is as good as his word.

Renton has warned me that he will attempt a character assassination on her, and she is right. According to Taylor, he could not have treated her better – he gave her a job, bought her a car, "looked after her better than my fiancee" – but had to let her go after two months because she was not up to the job. He admits he met her through Rape Crisis, but never suggests that she was vulnerable. Instead, he simply states that she set out to ruin him and has cost him his film career. As for the money he owes Renton, he insists he has paid it back.

I tell him she says he was never an editor at EastEnders. He looks affronted. "I've still got all my payslips, contracts, everything. Like I say, I still work with Leslie Grantham now. He's coming here for dinner on Friday night. He remembers our time together well." (EastEnders told the Guardian: "EastEnders has never employed Richard John Taylor as a 'chief editor', nor in any capacity on the programme. As soon as we were made aware of these allegations, we were of course extremely concerned, and the BBC Investigations Service immediately met with the complainant and offered their full support, as well as facilitating contact with the police. The BBC have also reported this matter to the police and have continuously given help and guidance as much as we can within our jurisdiction.")

What about the cheque to Renton that bounced? "I paid her in cash after that," he says. "You're talking about a woman who professes to have a law degree but has never gone down the legal route. Why didn't she take out a CCJ if I owed her money?" (Renton insists she has not received any of her money, that she left the job of her own volition and that Taylor never bought her a car. She also sends me a copy of a county court judgment she obtained against him.)

Does he think Long and Stone have cause for grievance? "Yes, because I have their money and it's long overdue." Sure enough, he blames Renton: he says that because she has destroyed his reputation by telling people he is a conman, various projects have fallen through. Will Long and Stone get their money back? "100%."

Is it true that ITV had guaranteed Acceptance for £420,000? "Yep, that was when it was Hazell." But the more he talks about it, the less it seems to be a guarantee. "I've still got the email from Thames Television saying, if you produce this, this is what we estimate it will be worth."

It would be great to see the email, I say.

"Well, I'll have to dig it out, because this is going back two years now." (He fails to produce the email, which is not surprising, since Thames Television ceased trading in 1993. When asked about Taylor's projects, ITV told the Guardian: "ITV has no record of either commissioning or contributing towards a project titled Acceptance or Hazell.")

What about the production company with Louis Theroux? "That was pitch stage," he concedes. "That's my brochure. It's one of those things where we say, if we can raise this money, this is what we could do, and it didn't work out this way."

So the company didn't exist? "No, but we would have set it up once we got the money together."

Would Theroux be happy with him obtaining money using the Taylor Theroux Limited name, I ask Taylor. "No, I had only two conversations with him. If you went to an agent and said, 'Can we put X's name to this?' they'd say no, you need to get the money. But if we went to get the money, they'd say we haven't got X yet. It's a double-edged sword." Is what he did wrong? "Yes, morally, but that's the way we have to do it."

Theroux told the Guardian: "I don't know anyone by that name, and don't have a production company with him or anybody else."

Taylor agrees to have his photograph taken. Within seconds, he has taken control, and is directing his own downfall. "I suppose I should look sympathetic if I'm talking about how I owe these people money," he says. We're discussing the fictional Taylor Theroux company. I tell him that's why his investors think they gave him money under false pretences. He umms and ahhs, and agrees it's not wholly transparent. "But if the project had worked, it wouldn't have been an issue, even though the circumstances under which the money was raised were still the same. That's how we do it." Are they right to feel duped? "They're bang to rights, but that's a standard practice in raising money in the independent film game. The film industry works on smoke and mirrors. Otherwise we'd never do anything."

Of the other names Taylor used to attract investment, Hugh Grant told the Guardian: "I have no memory of Richard John Taylor and I have not made any promise to appear in a documentary about Chris Langham." Steve Coogan told the Guardian: "I've never heard of him or his documentary." Both Coogan and Grant expressed their dismay that their names would be used to give credibility to the idea that a man convicted of downloading child abuse images could be regarded as a victim of press intrusion.

I ask Renton, Long and Stone what they would like to happen now.

"I want all my money back, and I want to see right done," Long says.

"To be honest, I think Taylor should go to prison," Stone says.

"Yes," Long agrees, "I'd like him to go to prison."

Renton says that what she finds hardest is that Taylor has undone all the good work she had done in rebuilding her life. She finds it difficult to talk about him without crying. "He knew I was vulnerable. I wrote a book because I didn't want to be a victim, but he's made me into a victim again."