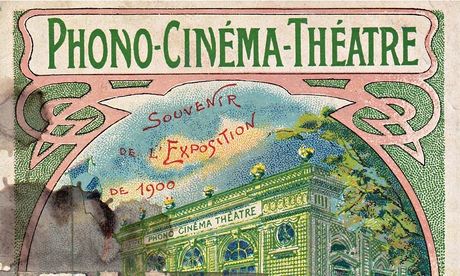

The 50 million visitors who flocked to the Paris Universelle Exposition in 1900 were treated to some stunning sights – from the world's tallest ferris wheel to the newly completed Eiffel tower. But one of the exhibition's most popular attractions was the Phono-Cinema theatre, which every day offered screenings of 41 short films, showcasing the most famous stage performers of the time.

For some visitors, the draw was simply the chance to watch moving pictures on a screen – this was only a few years after the birth of cinema. But for others, the miracle was seeing the likes of the actor Sarah Bernhardt, music-hall clown Little Tich and ballerina Carlotta Zambelli as if for real.

These artists were celebrities of the belle époque, photographed, gossiped about and idolised. And at the Phono-Cinema theatre they were singing, dancing and clowning across the screen, for anyone to see. Some of the films were colour-tinted, some had synchronised sound, and for many in the audience the experience was as close as they would ever get to seeing these stars perform.

If those 41 films were a marvel then, they remain so today.

Thanks to a collaboration between Gaumont Pathé archives, La Cinémathèque Française, and sound-recording expert Henri Chamoux, 34 of the original films have been beautifully restored. And such is the clarity and vibrancy of the result that we don't only get startlingly vivid views of these legendary performers, we also get an uncanny inkling of what it might have been like to watch them, in Paris, over a century ago.

There's a screening of Phono-Cinema-Theatre at the Flatpack film festival in Birmingham later this month, performed to live music, just as the original films were.

And while the restored footage is not online, some grimier, murkier snippets do exist on YouTube.

Reading on mobile? Click to view

Here, for instance, is the 56-year-old Sarah Bernhardt playing the final scene in Hamlet – leggy, glamorous and autocratic in her doublet and hose, and for all the slow formality of the duel, displaying a marvellously adroit sword technique.

Reading on mobile? Click to view

Here, in witty, relaxed contrast is Little Tich. Born Harry Relph, the English clown was 4ft 6in tall (it was his name that coined the slangword titchy), but once he was wearing his specially customised 28-inch boots, he displayed an extraordinarily physical versatility, even a vertiginous version of dancing on pointe.

The real toe dancers, the ballerinas, in this Phono-Cinema footage, are dominated by Carlotta Zambelli, who was considered one of the most brilliant technicians of her day (she caused a sensation by executing 15 fouetté turns in Paris in 1896). On film she dances two clips including the pizzicato variation from Sylvia, and what's even more fascinating than the vitality, bounce and speed of her dancing is how intimate and easy her performance style is. As this snippet of Zambelli (spliced midway through the clip) illustrates, she can seem more like a music-hall dancer than a ballerina.

Reading on mobile? Click to view

But in turn-of-the-century Paris, ballet was very close to music hall. Audiences at that time were hungry for gaiety, exoticism and sex. More than half of the nine featured ballet films are novelty acts, overlaid with faux Javanese or Russian style or performed in historical costume such as the Danse Louis XV (performed by the sister act of Blanche and Louise Mante, who were painted by Degas, and adored by the public).

Just as famous then, although virtually forgotten now, is Jeanne Chasles. A dancer of bounding jumps, tough little pointes and a 100-watt smile (as evidenced in her solo from the 1899 ballet Le Cygne), she became one of the era's great teachers and also one of its few female choreographers. Chasles cared passionately about her work, so much so that in 1925 she brought a suit against the Paris dancer Olga Soutzo for the wilful misinterpretation of her choreography. Chasles's success in court brought her a degree of international notoriety, and clearly she was a remarkable women. Successive generations of dancers can count themselves lucky, however, that the case didn't establish a legal precedent.

The Flatpack film festival runs from 20-30 March 2014 in Birmingham