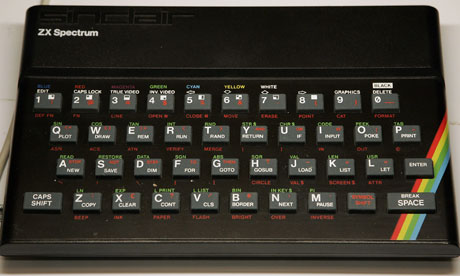

Celebrated today in a pitch-perfect Google Doodle, the 30th anniversary of the ZX Spectrum will have many veteran gamers swooning into a reverie of eighties nostalgia.

Released on this day in 1982, the machine typified the British approach to industrial design – utilitarian but also idiosyncratic and characterful. It should have been buried by its more powerful contemporary, the Commodore 64, but somehow this strange little slab of plastic and rubber earned itself a considerable slice of the nascent home computing market, especially in Britain.

Partly its success was about price. Since the launch of the ZX80 computer two years earlier, restless British inventor Clive Sinclair had been interested in computing for the masses.

Using cheap components and a minimalistic approach to design, he was able to manufacture machines at a lower cost than rivals such as Acorn, Apple and Tandy. The computer's rubber keys, for example, were created from a single sheet, with a metal overlay to separate them – much less expensive than producing a conventional keyboard.

So while the BBC Micro started at £235 for the Model A option and the C64 hit the shelves at around £350, the Spectrum launched at just £125 for the 16k version or £175 for the mighty 48k.

At a time of deep recession, with unemployment at 3 million in the UK, this was a vital factor – especially as a lot of the interest in home computers was coming, not from businessmen who wanted to do spreadsheets at home, but from kids, excited by the possibility of writing and playing cool arcade games in their own living rooms.

"The key thing was price for us," says Ste Pickford, who together with his brother John, started out writing computer games in the earlier eighties.

"We spent a full year with this massive jar in the house labelled 'Spectrum savings fund'. We put every spare bit of pocket money we had into it. £175 was way more than what mum and dad would have been able to afford on a Christmas present, but we wanted it all year.

"We must have saved up £80, and our parents were just about able to put the rest in. So the price was everything. It was the only way a family like ours could have owned a computer."

There was also a fundamental difference in philosophy – while his competitors were still producing hardware with serious computing interests in mind, Sinclair was targeting the mass market; he saw the wider consumer appeal of computers, not just as serious workhorses for home accounting, but as gadgets that could be as ubiquitous and easy to use as the TV or pocket calculator.

"Computers were quite scary at the time," remembers Philip Oliver, co-founder of Blitz Games Studios and one half of the Oliver twins, who created the legendary Dizzy series of games on the Spectrum.

"Some people were actually worried they were going to take over the world, thanks to movies like WarGames, other people worried that computers were going to steal their jobs. What the Spectrum did was gave a friendly, fairly simple image to computing. There was nothing frightening about the Spectrum!"

Ironically, there were strengths too in the technical limitations of the hardware. The Commodore 64 was more powerful and capable – its multi-chip architecture had been designed to move coloured sprites around the screen as quickly as possible – but it also did some of the work for the coders.

"When we started at the development studio Binary Designs we noticed that, actually, a lot of the C64 programmers weren't that good," says Pickford, now running digital publisher Zee-3, responsible for the Bafta award-nominated puzzler Magnetic Billiards.

"We realised that machines like the C64 had a lot of clever hardware; they did a lot of the hard things – like scrolling and sprites – for you. You could get most of the way to having a game running without knowing that much.

"The Spectrum had nothing. Architecturally, it was a really simple machine for a programmer – it was just a load of Ram and a processor; and the screen itself was just dealt with as part of the ram. You had to do everything the hard way, but it meant that if you managed to get a sprite moving around on the screen, you'd done a lot of really clever stuff.

"Years later, when that generation of coders grew up, Britain was really punching above its weight in the PlayStation era, when you had the start of games like Grand Theft Auto. The Spectrum bred a generation of really smart programmers."

This blank slate design also meant that developers weren't steered toward creating conversions of established arcade titles – they were free to improvise. Hence, the surreal Python-esque platform puzzlers Manic Miner and Jet Set Willy, created by eccentric lone coder Matthew Smith; hence, the beautiful and challenging arcade adventure, Head over Heels, by Jon Ritman who introduced the concept of controlling two different characters.

There were also bizarre experiments like Mel Croucher's Deus Ex Machina, an adventure about life emerging from a computer, which came with an audio tape featuring Ian Dury and Doctor Who star Jon Pertwee.

The ZX Spectrum held its own in the format wars until the late eighties, and developers were pushing the tech to the very end.

For example, the initial inability to properly colour sprites without bleeding out into surrounding space (thanks to the way the Spectrum handled colours as 8x8 pixel cells), was defeated in games like Trap Door and Dizzy through the use of thick character outlines and large sprites.

But the machine didn't prosper outside of the UK, and with the arrival of 16bit behemoths like the Commodore Amiga, as well as specialist consoles like the Nintendo NES and Sega Master System, Sinclair found itself unable to compete.

But for those thrilling years between 1982 and 1988, against other machines designed to push objects around screens, the Spectrum symbolised and amplified a peculiarly British approach to technology; it was about lone mavericks, doing their own thing, figuring stuff out, inventing their own conventions.

Certainly, the Commodore 64 produced plenty of genius coders, artists and game musicians, but the Spectrum arguably fostered something else – something that the Raspberry Pi initiative is now attempting to re-capture – an approach to computer hardware that is more about exploiting the machine, testing the architecture, probing at the metal and silicon innards, rather than trusting to high-level languages and application-programmer interfaces.

Writing for the ZX Spectrum was more about invention than design. It was a blank slate on to which a large section of the British game development industry drew itself.