'People were terrified of him, as though it was the lion's den," the Vogue model, Dorothy McGowan, said of working with William Klein back in the 60s. At 84, Klein has mellowed somewhat, though he still tells it like it is. "People ask me why I never went back home to America," he says, when I meet him in his apartment overlooking the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris. "Have you seen those crazy right-wing assholes who want to be president? The place is so reactionary it just makes me angry. If I lived there, you wouldn't be interviewing me, I'd be dead from a heart attack by now."

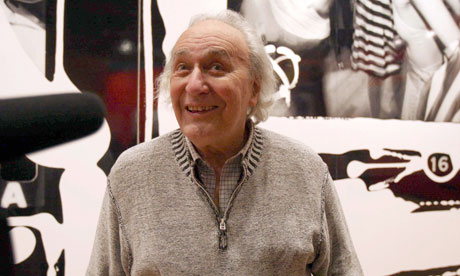

Wearing patched, faded denim jeans and a baggy jumper, his mane of white hair thinner now, Klein moves slowly and unsteadily around his spacious but cluttered living room, still stiff from a recent knee operation. His eyes are bright and mischievous, though, and there are glimpses of the confident-to-the-point-of-arrogant young man who ranks as one of the great iconoclasts of postwar American photography. "I'm an outsider, I guess," he says of his groundbreaking early work. "I wasn't part of any movement. I was working alone, following my instinct. I had no real respect for good technique because I didn't know what it was. I was self-taught, so that stuff didn't matter to me."

Having fallen in and out of fashion with galleries over the years, Klein is finally having a moment. Last week, he was given the outstanding contribution to photography award at the 2012 Sony World Photography Awards – work by award winners, including Klein, is on show at Somerset House. In October, Tate Modern will devote a big retrospective show to Klein and the Japanese photographer, Daido Moriyama, exploring the often similar ways in which they each depicted New York and Tokyo. "I think it's kind of stupid," he says, shrugging, when I mention how intriguing the show sounds, "but a lot of things happen without me really being involved. There's a connection all right, but…" He trails off and shrugs some more. One senses that he would have preferred a big London show all to himself, but does not have the energy to kick up the kind of fuss about it that his younger self would have done.

Klein burst on to the photography scene in the early 60s with a series of books about cities – New York, Rome, Moscow and Tokyo – filled with raw, grainy, black-and-white photographs that caught the energy and movement of modern urban life with scant regard for traditional composition. The first, Life Is Good & Good For You in New York (1956), once it got published, earned him the opprobrium of both critics and other photographers alike. "They just didn't get it," he says. "They thought it should not have been published, that it was vulgar and somehow sinned against the great sacred tradition of the photography book. They were annoyed for sure."

The book has long since been recognised as a classic that, alongside Robert Frank's The Americans, broke with the tradition of brilliant but understated observation, as exemplified by Henri Cartier-Bresson. Then, in 1965, just as suddenly as he had picked up his stills camera, Klein discarded it to become a film-maker, making fictional satires of the fashion industry (Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?) and the America right (Mr Freedom) and documentaries on the likes of Muhammad Ali and Little Richard. He did not return to photography until the early 80s. "I thought I had done what I could with it. I wanted a new challenge and film was certainly that, mainly because they never gave me big budgets." He shakes his head as if still baffled by the very notion. "I guess I wasn't really Hollywood material," he says finally, grinning his mischievous big grin.

Instead, he has always been an artist who follows his instincts, whatever the costs. Apart from a stint in New York from the mid-50s to the mid-60s, Klein has lived in Paris since 1948, when, having served in the US army in Germany and France, he received an ex-serviceman's grant to study art at the Sorbonne. On his first day in the city, the Red Cross gave him a bicycle and a map. As he was cycling around, "trying to find all these places I'd read about in books", he saw a woman who literally stopped him in his tracks. "She was the most beautiful girl I ever saw," he says, his eyes lighting up, "I just had to go over and chat her up. She was all smiles, so I asked her out." She said yes, and they were together for more than 50 years. His wife, Jeanne Florin, died in 2005. "Everything I did, I did for her," he told a recent interviewer.

Despite his street-tough exterior, a residue of childhood as a Jewish boy marooned in a tough Irish neighbourhood in Brooklyn, he is, at heart, a romantic, something his long self-exile has deepened. At the Sorbonne, one of his tutors was Fernand Léger, a mischief maker who was at war with the bourgeois values of the university. "He told us not to worry about galleries and collectors, but to go out onto the city streets and paint murals." It was while photographing some interior murals he had made on movable panels – "big hard-edged geometrical paintings" – that Klein had the epiphany that made him a photographer.

"Somebody turned one of the panels when I was shooting on a long exposure, and when I developed the photographs this already abstract shape was a beautiful blur. That blur was a revelation. I thought, here's a way of talking about life. Through photography, you can really talk about what you see around you. That's what I've been doing ever since."

Klein's big commercial break came when Alexander Liberman, the legendary art director of Vogue, saw a small exhibition of his early abstract photographs in 1955 and offered him a job. "Those guys spotted raw talent and encouraged it. They were all Russian Jews in exile: Liberman at Vogue, Alexey Brodovitch at Harper's Bazaar. They had a knowledge of avant garde art and design that the Americans didn't have."

Klein returned to New York and worked for Vogue for 10 years as a fashion photographer, shooting models in the hustle and bustle of the New York streets. It was the first glimpse of his iconoclastic style, photographs full of blur, movement and grainy high contrast. He used long-focus and wide-angle lenses as well as flash, less interested in the clothes than the atmosphere. "They were probably the most unpopular fashion photographs Vogue ever published," he says proudly.

Sensing his restlessness, Liberman offered to finance a bigger, more ambitious project. Klein told him that he wanted to shoot New York in a radical new way, maybe even try to make a kind of impressionistic diary of his wanderings on the streets. Vogue financed the project and provided him with a dark room and a budget for materials. The New York book grew out of this experiment. Klein was, he said later, "in search of the rawest snapshot, the zero degree of photography". He also described himself as "a make-believe ethnographer, treating New Yorkers like an explorer would treat Zulus".

Given his approach, was he surprised that people were shocked by Life is Good & Good For You in New York, which was first published in France in 1956? "Not really. I was showing what they didn't want to see. I was reacting against this romantic idea of New York – the Big Apple and all that. See, for me, New York was like a big shithouse." I look surprised and he grins widely. "Of course, New Yorkers think it's the centre of the earth. My father was like that. He used to go on about how it was the greatest city on earth, the land of opportunity, even though he had a lousy job and never really made it. [His father's clothing business went bust in the financial crash of 1928.] He was like the guy in Death of a Salesman, but all he could talk about was the land of opportunity. I didn't buy that crap."

Klein's New York book did not find an American publisher for several decades. Between 1960 and 1964, he published three others, Rome, Moscow and Tokyo. Then, bored and restless once more, he started to make films.

Klein had worked as an assistant on Federico Fellini's Nights of Cabiria in 1956 – "I just called his hotel and said, 'I want to speak to Mr Fellini' and they put me through" – and as artistic consultant on Louis Malle's Zazie dans le Metro in 1960. Inspired by the French new wave and the films of Chris Marker, he set about biting the hand that had fed him, making Who Are You, Polly Maggoo?, a wacky satire on the fashion industry. It starred his favourite model, Dorothy McGowan. "She was a tough little Irish girl from Brooklyn. Learned French and then learned her lines. She was like Alice in Wonderland in Paris, they loved her, but she wanted Hollywood." What happened to her, I ask. "She got married to a prick," he says, grimacing.

He went on to make some great documentaries, including Muhammad Ali: the Greatest (1969), Eldridge Cleaver: Black Panther (1970) and The Little Richard Story (1980). Was he, I ask, a radical? "I was left wing, for sure." he says "But I had no agenda with the films. I took it as it came. I was drawn to great characters and those guys fitted the bill, though Little Richard was a little bit different."

I put it to him that the film should really have been called In Search of Little Richard.

"Yeah, he disappeared on us. He was crazy like that. We organised a Little Richard day in his home town, Macon, Georgia, and he didn't show up." Did you fall out? "No. I got on well with him, but he was managed by these white hustlers who were like a mafia. They wanted him to endorse a bible for black people. They said: 'We're gonna organise your big comeback, but no crazy hairdos and no wild costumes.' The thing is, without that stuff, there was no Little Richard. He knew that, so he just disappeared. It was a crazy scene, but I had fun." This, you suspect, is the real story of William Klein's life: work as fun, with a little bit of confrontation thrown in.

He returned to photography in the 80s, when he was finally recognised as a pioneer – his early books influencing generations of photographers in Europe, America and especially Japan. He has since been garlanded with awards, and is also recognised as an iconoclast of graphic design, mainly through the use of the bold red and black swipes of paint he often applied to his enlarged contact sheets. Alongside his Tate Modern show in October, his London gallery, HackelBury, will host an exhibition of his art, William Klein: Paintings Etc. "It's a lot of stuff that no one has seen before," he says. "So, who knows, I might surprise people all over again."