As the author of nine novels (the most recent, The Detachment, published by Amazon) and four self-published works, I've long been curious about why so many people are frightened of a potential future Amazon monopoly while simultaneously so sanguine about the real existing monopoly run by New York's so-called Big Six. And it's been interesting for me to see people try to explain away the evidence of collusion between the CEOs of the major publishers as set forth in the US Justice Department's suit against these publishers and in the equivalent suit brought by 16 states. Have a look yourself, if you haven't already, and imagine the reaction if these sorts of meetings and discussions were happening instead among, say, Jeff Bezos, Tim Cook, and Larry Page, or among the heads of Bank of America, CitiGroup, and Morgan Stanley.

Of course, we shouldn't rely on Justice Department allegations alone to form the opinion that legacy publishing is a cartel (after all, this is the same Justice Department that hasn't prosecuted a single high-level US official for torture or a single banking executive for fraud, and that argues President Obama has the power to execute American citizens without recognisable due process). We can also look to the results of the legacy model: high book prices, most recently enforced via the so-called "agency" model; "windowing", whereby consumers who want cheaper paperback or digital versions are forced to wait until long after the release of the high-margin hardback; digital rights management regimes that annoy consumers and do little to inhibit piracy; increasingly draconian rights lock-ups in publishing contracts; lockstep digital royalties of only 17.5% for authors.

If you ask legacy publishing's defenders, "Which is the monopoly: the entity that charges high prices and pays low royalties, or the entity that charges low prices and pays high royalties?", you'll be told by those defenders (tortured logic to follow) that of course it's the latter. If you're a customer of Amazon, novelist Charlie Stross wants you to believe that in fact Amazon has you in a "death-grip". If you love books and like buying them from Amazon, Authors Guild president Scott Turow argues that in doing so you and Amazon are "destroy[ing] book selling". Enjoy your Kindle? More legacy insiders than I can count will accuse you of participating in the degradation of "literary culture", an Orwellian euphemism for "current literary establishment of which I am a member and with which I identify".

I wasn't around for previous technology-driven disruptions of industries, but I'm confident that as cars displaced horse-drawn carriages, electric lights displaced candles, and digitally distributed music displaced CDs, to name just a few, the establishments of the day decried the newcomers' methods and aims and predicted that the new way would inevitably cause The Destruction of Civilisation and the End of All That Is Good. And yet the doomsayers' predictions have never come true. In all these transitions, something was lost, but more was gained. The same dynamic is now playing itself out as a hidebound and moribund publishing industry, notable chiefly for its decades-long failure to involve itself in even a single innovation, is displaced by something more efficient and effective. And the dynamic will go on repeating itself, again and again, long after the legacy publishing industry has gone the way of the icebox, the telegraph, and the Vulgate Bible. As internet guru Clay Shirky recently put it, "Institutions will try to preserve the problem for which they are the solution," and in this regard legacy publishing is in no way unique.

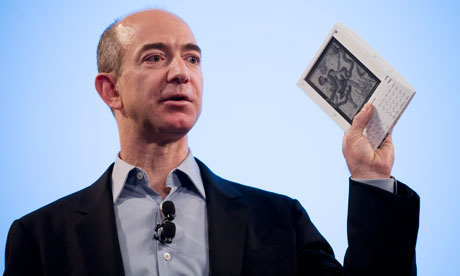

Though I'm certainly rooting for legacy publishers to successfully adapt (and why wouldn't I? When someone is sick, you don't want him to die; you want him to get well), I also think Amazon has been an enormous boon to readers and authors. Does anyone really believe that, without Amazon's innovations, readers would be paying less, or authors making more? Or that there would be remotely as big and vibrant a digital and self-publishing market for books if Amazon hadn't blazed the trail with the Kindle, the Kindle Store, and digital self-publishing?

Now, will Amazon break up the current publishing cartel only to become a monopoly itself? I doubt it. The company's DNA is all about serving customers, for one thing; for another, unlike in the analogue world, on the internet the competitor who wants to eat your lunch is always just a mouse click away, and with competitors like Apple and Google, I expect Amazon will be forced to stay true to its customer-centric roots rather than attempting to rely on the kind of monopoly rents that have poisoned legacy publishing's willingness and ability to compete. In the meantime, the publishing establishment wants you to believe that in order to prevent Amazon from possibly one day charging higher book prices, the establishment has to charge you higher prices today. Or, to put it another way, "Hey, you might get robbed if you carry all that cash around, so I'll just save you the trouble by taking your wallet right here." This isn't an argument; it's a con job. Consumers ought to recognise it as such.