This could be the least glamorous wrap party in the history of cinema. It is 2am, and we're sitting around a dying fire, sipping tea and whisky in the middle of a pine forest in Aberdeenshire, in the junk-strewn courtyard of an old farmhouse. The house belongs to Jake Williams, wiry, bright-eyed and with an impressive white beard. He's the movie's star; or, rather, he's the only person in it. Opposite him sit the crew: director Ben Rivers and sound recordist Chu-li Shewring. That's it. They have just finished shooting the final scene of Rivers' first feature: a close-up of Williams staring into the fire as it slowly dies. They've shot it twice tonight, adding bits of car tyre (it gives off a nice, bright light), fanning the smoke away, then strategically damping it down again with a watering can. As the first glow of dawn creeps up on the starry night, though, Rivers goes quiet. He isn't convinced he's got what he wanted. "You know what?" he says tentatively. "I think we need to do it again."

It should be clear already that Rivers is not planning on storming Hollywood. The exact opposite, in fact. He prefers to shoot on an old, wind-up Bolex camera with black-and-white, 16mm film, which he then develops back in London in his kitchen sink. He has made some 20 shorts over the past decade, and they are generally free of narrative, drama and character development. You're most likely to have seen his work in an art gallery or at a film festival – though that's set to change with the release of Two Years At Sea. "Too much exposition is the kind of thing that makes me bored with Hollywood movies," he says. "I like films that leave a lot to the audience."

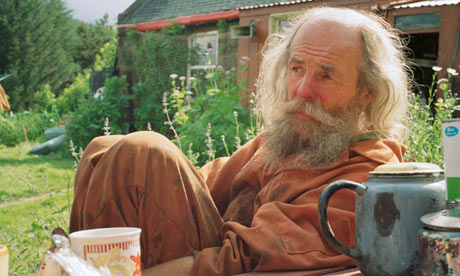

Two Years At Sea should give viewers plenty to do. Nothing is explained: who we're watching, where he is, why he lives like this, whether it's real or not. Even the title is a mystery. In the film we see Williams going about his lone existence: making coffee, having a shower, reading a book. Except nothing about this man's life is ordinary. His house is a cross between a bric-a-brac shop and a municipal dump, every corner filled with old books and records, tools, farm machinery, skis, oil lamps, woodpiles. And around his small plot are decaying caravans filled with even more junk. His "shower" is a system of hoses and taps rigged up by the kitchen window. It doesn't matter. There's no one else around.

Rivers' film presents Williams' life as a fantasy of perfect solitude, of complete freedom in a land of do-as-you-please, with nothing to do and all the time in the world. Alternatively, he could be the last man on earth – a rural Mad Max scavenging through the detritus of a dead civilisation. Rivers is often drawn to people like Williams, eccentrics and outcasts who have created their own realities far from civilisation. Ah Liberty from 2008 shows us a similarly free-range family in the Scottish wilds. I Know Where I'm Going visits a backwoods-dwelling geologist. "They're all fiercely individual," Rivers says of his subjects. "I'm interested in worlds people have created – very specific, hermetic worlds that haven't needed to conform to perceptions of the way we should live."

His repertoire became more overtly sci-fi last year with Slow Action, which reimagined four islands in different parts of the world as post-apocalyptic societies created by rising sea levels, described in voiceover by sci-fi writer Mark von Schlegell. "They're looking much more into the future than into the past," Rivers says of his films, admitting to a certain apocalyptic tendency. "I think it's on a lot of people's minds: we live in a seemingly pretty unstable world, with too many people. But I always think of myself of being pessimistic in a short-term way but optimistic in a long-term way. A lot of my films are full of hope, I think."

An art-school graduate and co-founder of Brighton's eclectic Cinematheque, 40-year-old Rivers knows cinema back to front, but he was also inspired by literature such as Francis Bacon's The New Atlantis, and in particular Norwegian author Knut Hamsun and his novel Pan, which also concerns a man who lives alone in the woods. Years ago, Rivers even went on a Pan-inspired pilgrimage to Norway to look for woodland hermits to film. He didn't find any. But on his return a mutual friend told him about Williams, who became the star of Rivers' first film in this vein, the 2006 short This Is My Land.

From there, the other subjects came to him by word of mouth. When Rivers received a commission to make a £35,000 feature – from the Film London Artists Moving Image Network – he returned to Williams. "I felt like there was a lot more to be done there," he says. "We already had this friendship. And I know how to deal with him. I know I can ask him to do something on Monday, and maybe after a week, he'll get round to agreeing to doing it. It's just knowing someone's rhythm, and their limits as well I suppose."

Rivers' comments are a reminder that Two Years At Sea is a work of fiction. The Jake we see in the film is "an exaggeration," Rivers explains. He directed Jake like an actor. There are touches of surrealism, too. In what you could call the film's big special-effects sequence, one of Jake's caravans magically levitates up in the air while he takes a nap inside. When he wakes up and opens the door, he is up a tree. "Even if its a re-enactment of things he would ordinarily do, you're still fictionalising someone to an extent," Rivers says, citing the fact that documentary greats like Robert Flaherty and Humphrey Jennings also staged events. Flaherty's Nanook of the North

is actually pretty close to "mockumentaries" like Spinal Tap, he says.

The "real" Williams is not what you would imagine from his screen persona. He has friends, a daughter, a telephone, a computer, and a bottomless supply of stories. He travelled the world for two years as a merchant seaman – hence the title. When he returned, he had enough money to buy his house, where he has lived for the last 30 years. "I'd never describe myself as a hermit," he says. "I bought this house out here because I was sick of paying rent. I'd had some bad experiences with landlords." The junk-hoarding he puts down to "a bit of a wartime mentality. Save jam jars because one day you might decide to make jam." He is also a natural performer: he has played mandolin on stage with Mike Scott of the Waterboys and has clearly enjoyed his time as Rivers' star, even the late nights by the fire.

Since Rivers started making Two Years At Sea, a new term has found purchase in film circles: "slow cinema" – meaning the type of contemplative, observational movie where image (and soundtrack) takes precedence over conventional narrative. Bracketed into this category are international auteurs such as Béla Tarr and Apichatpong Weerasethakul, possibly with Tarkovsky and Antonioni the movement's spiritual forefathers. The term fits Rivers' work like a glove. At times, Two Years At Sea almost slows to the stillness of a photograph, with just a tiny amount of motion in a static image to let you know time is passing – some socks blowing on a washing line, or a cloud drifting across a woodland landscape.

Two Years At Sea won a prize at the Venice film festival last year, but it has also been described by reviewers as formless, opaque, even soporific. Rivers' work could perhaps be seen as the flipside to literature: when you read a book, you're given a plot and you conjure the images in your imagination; with a film such as Two Years At Sea, it's the other way round. Its carefully composed images capture a poetic beauty that's rich with meaning and mystery, while the blotches and scratches and flares of the film itself add another layer of activity. There's always something happening. At the end of the film, even Williams himself nods off a little. It closes with that long, long shot of him staring into the dying fire. As the image fades to darkness and he stares into the fading flames, he struggles to keep his eyes open. The "one last take" turned out to be exactly what Rivers was after. They got there in the end.

Two Years At Sea is released in the UK on 4 May.