You could write yourself straight into Pseuds' Corner trying to describe Joey Barton. At the very least, you could give yourself a serious ache in the brain. Because although the barest of summaries – say, "Barton is a battling midfielder with a troubled past and a mammoth Twitter following" – doesn't come near to capturing the complexity of either his character or of our reaction to him, probing further leads you into decidedly muddied waters: into a personal and professional history studded with exhaustively documented controversies, from minor spats to serious violence, and a present in which @Joey7Barton's rapidly evolving persona attracts more column inches than his performances on the pitch. It leads you down tributaries in which our obsession with contemporary football seems riddled with class confusion, latent aggression and barely concealed schadenfreude. And it leads you back to a man intent on telling you that whatever you thought you knew about him is probably wrong.

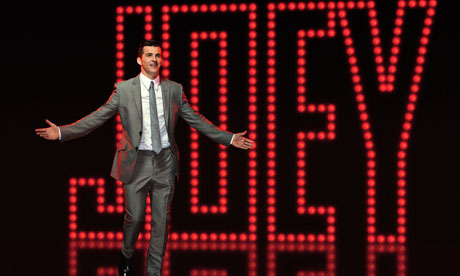

Even his name. "Joey", he tells me when we meet for the first time, is just a "stage-name", something that got scribbled on a team-sheet early on in his career. Friends and family call him Joe, and he also seems fond of Joseph, which goes nicely with the retro-Brilliantine look currently enjoying a minor vogue among Premier League footballers – you can imagine Barton and Scott Parker, for example, kissing their sweethearts goodbye before jumping into their Spitfires and Hurricanes, though the quiffed hairdo might owe just as much to Barton's love of Morrissey.

In any case, Joe/Joseph/Joey is exceptionally pleasant in the flesh: funny, engaged, unstoppably chatty, entirely free from any of the puffed-up nonsense you might assume comes with millionaire-sportsman territory. Physically, he has a sort of wiry poise, often standing on the balls of his feet, but there is also something diffident, almost shyly polite, about him. When two young women, hardly able to speak for coy giggles, approach our table for autographs and a photo, my reflex is to wonder whether some nutty rule about image rights will get in the way; Joey just puts down his fish-finger sandwich, smiles sweetly and asks: "Is it Jemma with a J?" All the subjects that I'd envisaged requiring a certain delicacy to bring up – his stint in jail, his alcoholism, his notorious altercations with team-mates, his rows with successive clubs – rise to the surface with ease, usually brought there by him.

But we begin with Twitter. He first appeared on the social-media site last August and, until his self-imposed "Twitter sabbatical" last month, tapped out 4,598 tweets. He has used his break, which followed a fairly rocky period on the pitch, to work on his new website, which he will launch in the next few weeks. During those eight months on Twitter, Barton amassed a cool 1,366,505 followers (he himself only follows 105 people). The numbers don't tell the whole story, which is that he has constructed (aided, of course, by journalists and commentators quick to spot a good story) a highly distinctive identity.

He's waged wars – most noticeably with the powers-that-be at his former club, Newcastle United, which he left on a free transfer to Queens Park Rangers last summer. In November, he challenged the club's managing director, Derek Llambias, to take a lie detector test to establish who was telling the truth about his departure and issued a further warning to Llambias and, one presumes, club owner Mike Ashley: "If he's worried now, him and his fat mate should be sh*tting it, if I decide to write a book. There'll be no holding back on those 2 muppets." (NB, Llambias and Ashley: Barton is indeed writing his autobiography, with Times columnist Matthew Syed.) Also in his sights are the game's governing body ("Just received my weekly warning letter from the FA headquarters"); and the likes of Alan Sugar, former QPR manager Neil Warnock and the entire cast of TOWIE. The hashtag #helmets often follows tetchy and occasionally vindictive swipes at his detractors.

He's also involved himself with campaigns he feels strongly about, including a concerted call for signatories for the e-petition to force the government to release documents relating to the Hillsborough disaster, and he nearly fell foul of the attorney general when he tweeted extensively about the John Terry race row. And he's become known for a variation of what we might call Cantona's Seagulls: that moment when a sportsman – and particularly a footballer – dares to say something more elaborate than: "I thought the lads showed a lot of heart out there today." Setting the tone early on – "Sitting eating sushi in the city, incredibly chilled out reading Nietzsche #stereotypicalfootballer" – the 29-year-old Barton demonstrated an interest in philosophy, politics, literature and art so at odds with our previous conceptions of him that it was even suggested someone else was tweeting on his behalf.

In fact, he nearly gave the whole thing a miss. After months of just watching, he tells me, he thought: "No, not for me, I think I'm just too honest. It'd be like giving an arsonist a box of matches, me being on there. This could be really dangerous for me." What changed his mind, he explains, was wanting to be seen as someone other than "a monosyllabic Neanderthal who fights in city centres, drunk".

"For a long, long time I'd been portrayed as a certain type of person by the media and, of course, with certain elements of my character, they totally give them the ammunition. But I also felt that they were coercing me into being something that I wasn't, and maybe if I did 15 good things, they'd wait for the negative to say, 'Oh hang on, look he actually does fit the stereotype, he is the token bad boy of English football…' And I just got pissed off with it, really. I started thinking about how you'd be remembered and what I wanted to stand for, or what people would actually say when I wasn't in the room."

One thing you could say about Joey, in or out of the room, is that he's a pretty combative guy. One of his favourite words is "smite", as in someone (often a sportswriter) "having a smite" at him. Twitter, he argues, allows him to "smite" back. He remembers telling one journalist to, "Say what you want, your industry's dying and history's written by the victors", and "Your shitty newspaper columns, no one will remember them". "And they hated it," he tells me. "They would do," I reply.

The "elements" of his character that have provided the "ammunition" go beyond the traditional boozed-up footballer snapped out on the razzle with a glamour model the night before a big game. Over the past decade or so, as Barton progressed from Manchester City to Newcastle United to QPR, with a single England cap in 2007, a series of violent confrontations has blighted his career, earning him a reputation as a player with an uncontrollable temper (as he puts it, "the anti-Christ"). In 2004, he stubbed a cigar out in the eye of City colleague Jamie Tandy at the club's Christmas party; the following year, he was found guilty of gross misconduct after a disturbance in Bangkok with a teenage Everton fan. Then there was a training-ground altercation in 2007 with team-mate Ousmane Dabo, for which Barton received a four-month suspended sentence for actual bodily harm. And most seriously of all, he was found guilty of assault and affray following a fight outside a branch of McDonald's in Liverpool, a conviction that led to him spending 74 days in prison in 2008.

What was shocking about each of these events was not that a testosterone-fuelled, highly athletic young man with a short fuse got into a fight, but the severity of his reaction and the fact that he seemed to learn little from each incident. Talking to him about it now is a strange experience. On the one hand, he's keen to set some kind of record straight, explaining in detail the context that he feels went unreported, particularly the extent to which he was reacting to provocation. But just at the moment you feel he's missing the point – the newspapers, after all, didn't put him in prison – he begins to talk about what happened with an almost unnerving openness and gravity.

He describes growing up in Huyton, Merseyside, an environment in which aggression was the norm. "Where I'm from," he says, "if you said something to someone in the pub, they'd smash a glass over your head, or stab you or shoot you or you'd get beaten up." (This is not just swagger: Barton's brother Michael, after all, is currently serving a minimum of 17 years in prison for his part in the racially motivated murder of Anthony Walker in 2005. Barton, who had not lived with his brother since he was 14, when their parents split up, refused his brother money in the aftermath of the crime and publicly urged Michael to give himself up to the police.)

At 17, Barton was earning £300 a week – roughly the same as his dad. But football doesn't work like most of the rest of the world, with small fillips of achievement and good fortune and incremental rises in income. Before long, his pay was six grand a week, more than everyone in his family combined: "I'd go to nightclubs and queue up with my mates when I was on £300 a week, then all of a sudden everyone was giving me everything, I could walk to the front of nightclub queues, everyone knew who I was." Barton rarely draws breath during conversation, but he pauses as he considers what that felt like. "Hard to remain sane. Hard to remain balanced."

He began drinking, despite the fact that he didn't really like it. "I was a 22-year-old lad, I had 40,000 fans going to the game, and if I didn't play well, I was under this enormous pressure. And the only way I could deal with it, the only form of escapism, the only way I could get in touch with my inner self, who I remembered from before I was famous…

"Everyone was looking at me and judging me I felt. I'd walk into a room and everyone would know who I was and I'd never know who they were, and this paranoia set in. And the only way I could escape that was by getting pissed. I hated drinking. Even to this day, I don't like the taste of drink, I never have done, but I loved feeling drunk… the pressure would go, and then the likelihood was I'd wake up next morning and I'd done something stupid, told someone to fuck off, done something really ridiculous, in a drunken state, and made the pressures worse, because then I had to answer for whatever thing I'd said something out of turn to someone… and the vicious circle just started from there."

The cycle was add-ressed when he went to jail, a traumatic experience that he describes as "the making of me", aided by spells on anger-management courses and in counselling and at AA meetings. A lot of what he says is clearly inflected with the language of personal development and redemption. He talks repeatedly about his addictive personality, about the importance of learning balance, about how "the complete fuck-ups" in his life have enabled him to become who he is now. What's important these days, he says, is being happy with himself and being a good father; his son, Cassius, was born in December last year and, he says, he'd rather put his kids through school than buy a 50-grand watch. I suggest that he could probably do both. "Yeah, but what's the point? It only tells the time. You only need one watch. You only need one car. When does that stop, once you get into that?" He's never really been one of the bling footballers, has he? "No. I'm not a twat. To put it bluntly."

Barton's life off the pitch has been very much quieter over the past few years, but on the field of play and in the dressing-room, he still cuts a controversial figure. Before we meet, I have to have a stern talk with myself about not mentioning the game last August in which all Arsenal fans will contend that Barton got new signing Gervinho sent off on his debut; he's had similarly abrasive encounters since with fellow midfielders, Karl Henry from Wolves and Norwich's Bradley Johnson, the latter earning him a three-match ban. My questions about this kind of stuff are possibly the only time he tenses up: "I'm in a contact sport," he says tersely.

It's a response that will chime with football fans who fear the game turning into an over-regulated series of exhibition matches – what more do you want from your midfielders, after all, than a bit of blood and guts? But in Barton's case, one wonders how much his intemperateness has been detrimental to his football and to his progression in the game. In 2007, he spent 12 minutes on the pitch as a substitute as England played Spain under Steve McClaren. Subsequently, Fabio Capello indicated that he felt Barton was a "dangerous" player who couldn't be relied on not to get sent off. The call-up never came.

His clashes with those in authority show no sign of abating, although thus far he has been entirely circumspect about QPR's new manager Mark Hughes, a steely character who one imagines takes a dim view of players stepping out of line to air their opinions. Hughes's predecessor, Neil Warnock, wasn't so lucky: when he was sacked in January, Barton – his captain – at first appeared to offer his Twitter condolences ("Gutted to hear about the manager losing his job") only to liken him, a couple of weeks later, to hapless fictional England manager Mike Bassett.

His attitudes to his elders and betters (I can hear him snort at that "betters") at times seems fuelled by crude bravado. And it sits oddly alongside the rather more thoughtful way that he approaches other aspects of his life. He's almost as likely to be tweeting about galleries he's visited ("fell in love with John Singer Sargent"), the joys of changing nappies and his latest viewing and reading material (recent hits: Chomsky and Naomi Wolf). He talks about how Twitter has "really engaged my social conscience… no one's speaking about people, so I'm going to have to do it. I'm going to have to comment, because if I don't do it, no one else is going to do it." Not exactly true, but what I think he means is that he's able to connect with a whole phalanx of people who mightn't otherwise be thinking about NHS reform or the economy or what's on Question Time.

It would be easy to be cynical about his motives. Twitter, he tells me, made him look at himself from "a sort of brand perspective", and many have jumped on his attempts to reinvent himself, 140 characters at a time ("misguided arrogance," said the Daily Mail recently, "often just Vinnie Jones with Wi-Fi"). Even so, there's a subtext to much of the commentary that, if I were him, might make me quite angry. Because essentially, when he's now referred to as art-lover Joey Barton, or Nietzsche-quoting Joey Barton, or social-media philosopher Joey Barton, there's a sense that he's a) putting it on, b) taking the piss or c) getting a bit above himself. Which is really just another way of saying the bourgeoisie isn't quite sure what to do if someone working class goes to an art gallery.

And which is why, when he and I meet for a second time, we decide to go to the National Portrait Gallery and have a look at the Lucian Freud exhibition. "Intriguing character this fellow," he tweets, ahead of our outing – which, incidentally, we get to on the tube and follow with lunch that costs a grand total of £17.80. I mention it because I imagine most journalists dispatched for a day out on the town with a Premier League footballer would quake at the thought of their impending expenses claim.

If he's putting on his enthusiasm for art, he's making a pretty good go of it. On the way in, he tells me quite a lot about Freud I didn't know ("I'd have thought you'd have done your research, Alex") and once there, he's clearly immensely engaged, standing very close to pictures for a very long time. He's already told me that one of the things he thinks he can achieve on Twitter is to counteract the limitations placed on "kids from working-class backgrounds who've been told not to like art"; walking around a gallery with him for hours, I think he's probably got a better chance of doing that than Sky Arts or BBC4.

Mind you, you can never tell with Joey Barton. Shortly after our outing, I go abroad and have to do without internet access and Sky Sports News while I'm travelling. When I come back, I check in on @Joey7Barton to see what he's been up to. I'm vaguely aware that he's not been having the best time on the pitch; but then again, who does, when their team's hovering around the relegation zone as the season goes into its nervy run-in? But he's not there. On 24 March, a series of tweets voicing his feelings at being dropped from QPR's team – "Very, very disappointed", "Not selected" – culminates in the announcement of "a little Twitter sabbatical before I say something I'll end up regretting".

The following week, when Barton is back captaining the team and QPR beat Arsenal at Loftus Road, I think he might re-emerge, but no dice. Strangely enough, I miss him. Shortly afterwards, we meet up for a final time and he tells me about his new internet project. Twitter, he confides, has had its positive and negative aspects, but what he wants now is a space that he controls, "almost a self-publication". His plans sound ambitious – writing his own material, video content and, most importantly, the opportunity to bring people together: "For me, it's about being a hub, or being involved in helping people to kickstart conversations that maybe will help make a change for the better". He'll be back on Twitter, but more, one suspects, to draw attention to the website. "Sometimes," he reflects, "you can stay in a space too long."

In fact, Barton resists attempts to keep him in confined spaces – or boxes – for very long at all. So much about him – the repeated narrative of misdemeanour and rehabilitation, the outsider status he seems to crave and shun at the same time, the two-fingered salute to authority – makes you want to extrapolate, to reach some general conclusion about these multi-millionaire loose cannons that we've created, with their brilliance and their rages and their vendettas and their persecution complexes. And about the love that we bestow on them when they do what we want and the furious revenge we want to exact when they disappoint us. But I don't think you can. Barton is at once more intelligent and more unpredictable than many of his peers – and his demons have, over the years, pursued him more vigorously. And, the obvious: footballers are not as homogenous as we would like them to be. It comes down to this: Joey Barton is not Frank Lampard. Or Luis Suarez. Or Ryan Giggs. Or even Mario Balotelli. He's Joey Barton and, as he tells me with an earnestness that borders on the endearing, "I'm quite happy to say I'm fucked up. I'm peculiar and a weirdo. That's me."