Michael Hart is dead. Michael who? I guess most people have never heard of him and yet if you've ever read an ebook then your life has been touched by him. Why? Because way back in 1971 he had a great idea: that computers could make great literature freely available to anyone. He founded Project Gutenberg, the world's greatest archive of free, public-domain ebooks, and he devoted his life and most of his energies to that one great project.

The idea came to him when he was a student at the University of Illinois in 1971. Computers were then huge, fabulously expensive mainframes and Michael had access to one of them. On Independence Day 1971, inspired by receiving a free printed copy of the Declaration of Independence, he typed the text of the declaration into a computer file and sent it to other users of the machine. He followed it up by typing the text of the Bill of Rights, and then, in 1973, the full text of the US constitution.

Most people would have stopped at this point, but not Hart. If computers could store and endlessly distribute great texts, he reasoned, why stop at the constitution? Why not create the digital equivalent of the lost Library of Alexandria? Why not every book in the world – or at least every significant text that was out of copyright and in the public domain? Thus was Project Gutenberg born.

It's important to remember the date: 1971. In computing terms, this was the Neolithic Age. Granted, the Arpanet was up and running, but it was confined to a magic circle of universities and research labs.

The first usable personal computers wouldn't appear until 1977-8. The internet was still 12 years away and the web lay a full two decades into the future. IBM had just produced the first (8-inch) floppy disks and 5.25-inch commercial floppies were five years away.

Disk storage was limited and expensive, so Hart decided that texts ought to be encoded in the most compact format possible – as plain ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) characters. That meant no fancy formatting, no bold or italics – just the text. In this way, the US constitution could be packed into 281 kilobytes. And he chose the Bible as an early candidate for inclusion, not just because of its cultural importance, but because it was conveniently segmented into smaller, more manageable books.

Hart personally typed the text of the first 100 books in the archive, including the complete works of Shakespeare. As the project grew, others helped in an early example of crowdsourcing. In April 2002, The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci were added as the 500th book.

And so it went on. I've just checked the site. It has 36,000 ebooks currently available. The only concession to modernity is that Hart's insistence on plain ASCII has been relaxed; the texts are now available in formats for Amazon's Kindle, Android, Apple IoS and other e-readers.

Those who knew him testify that Michael Hart was an extraordinary individual – idiosyncratic, original, humane, determined and generous to a fault. He never made much money, repaired his own car, had scant faith in medicine and built most of his own electronic gear from stuff he picked up in garage sales. On Saturday mornings over breakfast in the local diner, he would work out the optimum route to cover the maximum number of garage sales that day; it was his version of the travelling salesman problem in mathematics.

In his obituary of Hart, his colleague Gregory Newby described him as an "unreasonable" man, in George Bernard Shaw's celebrated use of the term. "Reasonable people," wrote Shaw, "adapt themselves to the world. Unreasonable people attempt to adapt the world to themselves. All progress, therefore, depends on unreasonable people."

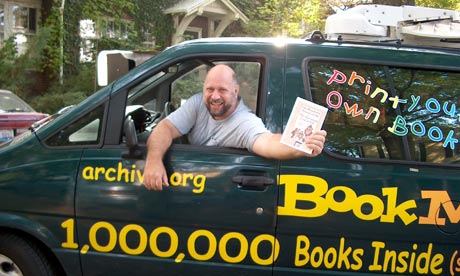

Shaw was right. As Brewster Kahle, founder of the Internet Archive, put it, Hart belongs in a very select group of other unreasonable men – people such as Richard Stallman, founder of the free software movement, or Ted Nelson, who campaigned for hypertext long before the web – who changed the way we think.

So next time you switch on your Kindle, or read an ebook on your phone, spare a thought for Michael Hart. May he rest in peace.