Cinema is very much a "sit-back" medium. It insists on entrapping you in a darkened space, force-feeding you a pre-assembled product and monopolising your attention for up to a couple of hours. Once, that would have been no problem. People were happy to sit through hour-long sermons or even stand through three-hour speeches when nothing more amusing was on offer. Then things changed.

Empowered by new opportunities, the vulgar herd sought to seize control of their entertainment experience. Comic books, which could be read at the bus stop or under the schoolroom desk, zapped the three-volume novel. Now, people select their own Twitter feeds and compose their own tweets. They organise their own viewing on YouTube, and create much of it, too. Videogaming, perhaps the archetypal sit-up, take-control medium, enables the consumer to become the hero of his or her own narrative.

Cinema still has its attractions. At least it offers a refuge from your partner's prattle if you have to go out on a date. Increasingly, however, conversation can be combined with texting or Facebooking, so a beloved's blather is no longer quite so irksome. Understandably, film-makers have begun to fear for the big screen's future. For a while now, they've been looking to more fidgety media to see what they can purloin.

Thus, plot and character have increasingly made way for incessant action and frantic cutting; but direct pilfering from competitive territory has also become routine. Comic-book and videogame protagonists have been pressed into the big screen's service. Yet up till now, the essence of the plundered media has not been successfully translated. Conscripted heroes have been teleported into traditional movie formats; the singular environments on which their appeal depended have had to be left behind. Because of this, the benefits of these transfers have been limited.

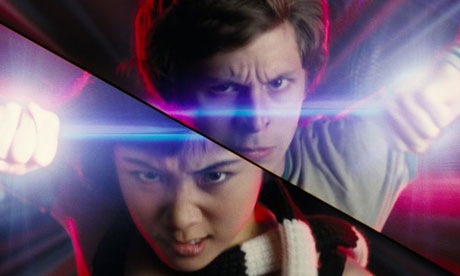

Scott Pilgrim Vs the World is different. It eviscerates a comic-book series, but seeks to achieve much more than nick its characters. In addition, it tries to import its source material's methods; then, it aims to mate them with those of the videogame. The plan's ambitious, and the result's striking.

Here are the captioned Brrings, Blams, Ding-dongs and Kerpows of the comic-book frame. So are the levels, points and sound-effects of old-style gaming. The atmosphere of both worlds is lovingly evoked, with endless knowing allusions in both sound and vision. The film's certainly different. In a way, it's delightful. Sadly, in America, it's also been a bit of a flop.

It's not too hard to see why this might be. The approach taken has required the banishment of the traditional staples of movie-making. There aren't really any characters, since no one can be more than a comic-book cut-out. There isn't much of a story. All that really happens are seven hand-to-hand fights. These are allowed no more relationship to physical reality than a videogame would permit. The humour drains them of threat. All they can be is balletic spectacles, their appeal dependent solely on their choreography.

That isn't really enough. After the second fight, the knowledge that there are five more to come induces mild panic. Comic-book and gaming fanboys may enjoy the witty references, but even for them the joke must surely wear thin.

Games work because the player controls the action. No film can deliver this effect. As a spectator sport, splattering deadly exes doesn't cut it: this pursuit demands participation. It's not only the gaming element that's in the end a letdown: so too is the comic-book dimension. Bryan Lee O'Malley's six-volume epic (let's start calling it a graphic novel) is full of subtlety and insight. Yet crunching its story into a quasi-videogame has managed to squeeze out most of its genius.

The moral seems clear. Traditional movies may tax the patience of ever more scatterbrained filmgoers. Captivating new media may threaten to lure them away. Nonetheless, film-makers shouldn't try to steal their rivals' clothes. It just won't work. They'll stand or fall by the strengths of their own trade.