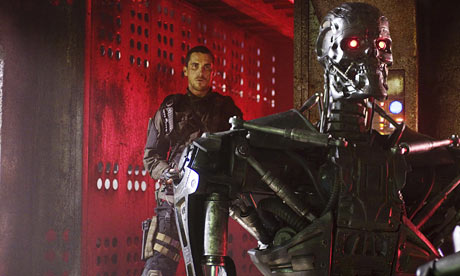

On the face of it, the hostility that Terminator Salvation has evoked seems a bit unfair. Its action outclasses that of better-received films, its devastated landscapes are striking and its plot is relatively cogent and comprehensible. Nonetheless, it clearly fails to excite. Something important is missing.

The film takes its franchise's war between men and machines to a new level by infiltrating the people's resistance forces with a human/cyborg hybrid. Unfortunately, the spectre thus paraded isn't remotely scary. After all, these days, few of us are racked by fear that machines will try to kill us.

A quarter of a century ago, when The Terminator hit the screen, things were a bit different. Then, advances in computing were a disquieting novelty to many. Hal's terrifying takeover of the Discovery still haunted cinemagoers' imaginations from 2001: A Space Odyssey. It was a time for murderous cyborgs. Now, however, we take artificial intelligence for granted. It's become humdrum rather than chilling.

Future global conflict was an all too real prospect in the era of the cold war. Post-apocalyptic, Mad Max worlds, like the one in which Terminator Salvation is set, were far from fantastical for a generation living in genuine terror of imminent nuclear holocaust. Today, our fears lie elsewhere.

Big-screen science fiction turned a minor literary genre into a mainstream mentor capable of explicating both our universe and ourselves. It not only disseminated abstruse ideas, but even prompted discoveries itself. At the same time, it has enabled us to reassess our society from the perspective of conceivable alternatives.

Our own age ought to provide it with plenty of raw material for the performance of these functions. Cosmology, sub-atomic physics and the life sciences are transforming our understanding of reality, while the way human life should be organised has come once more into question.

Yet, Hollywood continues to offer us sci-fi spectaculars that, like Terminator Salvation, seem strangely out of time. Star Wars: The Clone Wars was perhaps the most egregious example of an attempt to suck box-office dollars from the decaying corpse of a cold war masterpiece. Our decade's superhero sagas carry a whiff of nostalgia for the age of the comic book. Star Trek was a reminder that space was once the final frontier. We've learned since then that the frontiers that matter are closer to home.

The Matrix showed signs of originality, but was quickly turned into another burnt-out franchise. All that Angels & Demons could do with the Atlas experiment, which aims to undercover the origins of universe, was to suggest that antimatter might fuel a bigger explosion than the ones we've been used to.

Explosions are, of course, a large part of the problem. Action, effects and CGI spectacle have been allowed to squeeze out ideas. Geeks and popcorn-munchers may not have minded, but the reception of Terminator Salvation suggests that others may now be minding rather a lot.

New technical opportunities are often a mixed blessing. Some of the cheaply made sci-fi B movies of the 1950s may still hold lessons for the over-endowed movie-makers of today. One might be that science fiction needs more than whizz-bangery to succeed. This shouldn't be a surprising message. Action tends to be most effective when it clashes with the constraints of the real world. The terminators' near-invulnerability saps interest in their onslaughts.

We get hints of what more thoughtful science fiction might look like in films such as Children of Men. Like Terminator Salvation, this turned the world into a wasteland, but it didn't require the malevolence of machines to achieve this. Unfortunately, in that case, it wasn't clear what was supposed to be precipitating the drama. Still, if we want an apocalypse today, why can't we call upon financial collapse, bioterrorism or climate change? Why do we need cyborgs when we've got designer babies?

It's surely time film-makers reclaimed two of the genre's key ingredients: science and fiction.