Ella Bonner, 1872

Spirit photographers were prevalent in the 1800s when seances were popular and the greatest ghost stories of all time, such as Dickens's The Signalman, were being written. They managed to fool people out of pocket with images such as this obvious double exposure Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Another example of spirit photography, in which spectral presences were captured consoling their bereaved relatives at a time when mortality was high and grief a constant affliction Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Is this a famous Victorian 'freak' cruelly displayed like the Elephant Man? Of course not – it's a trick photograph Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

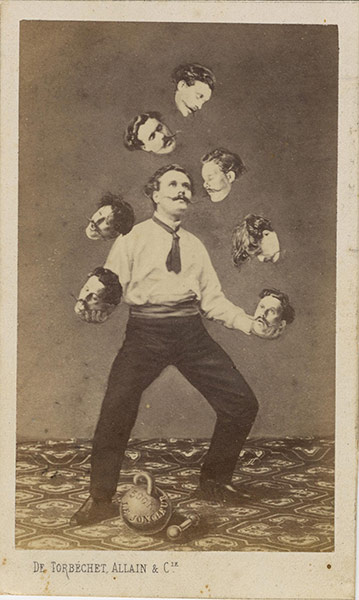

As early as the 1880s, photographs were being created simply to have fun with the truth. Images such as this man juggling seven of his own heads were not designed to be believed. They were to delight the imagination Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Simply by cutting and pasting photographs it was possible for pre-Photoshop wizards to create fantastic images such as this from the 1930s Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This photomontage imagines a sci-fi future for New York in which Zeppelins would anchor to skyscrapers. The Hindenburg disaster was to destroy that dream Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Arthur Conan Doyle used these images in a 1920 magazine article to finally prove the existence of the previously folkloric fairies. It was not until 1983 that two elderly Yorkshirewomen, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, admitted they had faked the pictures as children Photograph: Glenn Hill/SSPL via Getty Images

A tiny woman sits next to a giant man in this picture, created using the classic photomontage technique of inserting part of one photograph into another and rephotographing the results. Another image not seen to be believed … Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

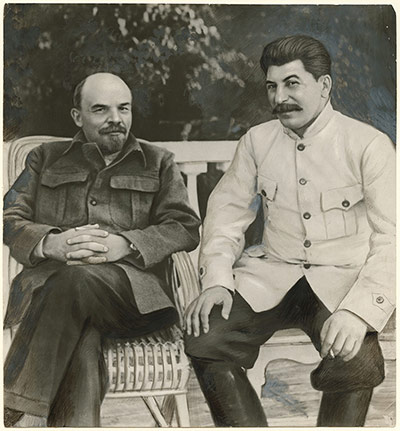

In a 1949 double portrait, the Soviet leader Joseph Stalin is seen as a young man with Lenin, the adored leader of the 1917 Russian revolution. Stalin and Lenin were close friends, judging from this photograph. But it is doctored: two portraits combined to claim Stalin as the true heir of Lenin Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

Photomontage was a gleeful satirical weapon, as this early anonymous example reveals. This kind of cut-and-paste political art was taken to radical extremes by Berlin dadaists such as Hannah Hoch and John Heartfield after the first world war Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

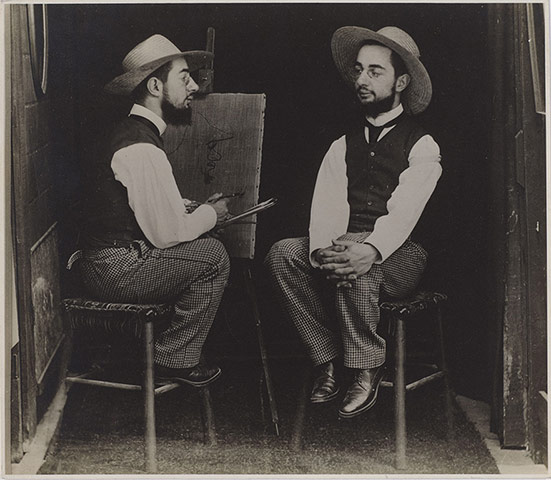

This late 19th-century fake image shows Toulouse-Lautrec sitting opposite himself waiting to have his portrait painted, an early example of surrealist art and a precursor to dadaist images to come Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

A photograph of a woman in a swoon is combined with other images, including a painting, to create this emotive picture of a husband distraught at his wife's death. It is a fictional photograph, a dramatic scene Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This is a classic surrealist photograph. Here, the techniques of fake photography are used to a serious artistic end as the image recreates the claustrophobia of a nightmare Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

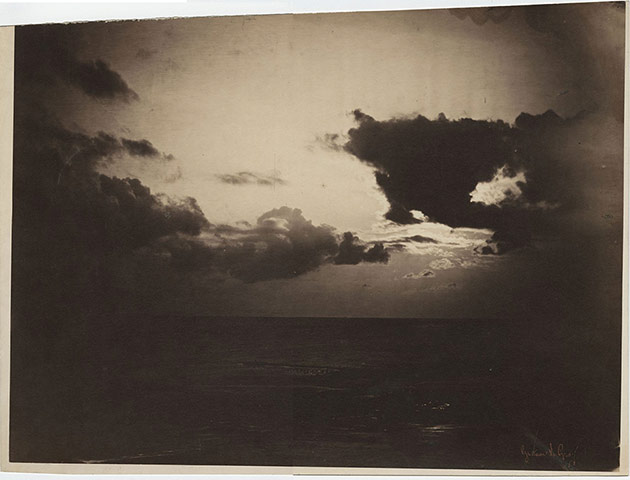

Photographers wanted to compete with fine art from early on in the medium's history, but found it hard to achieve proper exposure for both sea and sky in one image. For this beautiful picture, Le Gray ingeniously combines two negatives to create a grand vision of nature Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

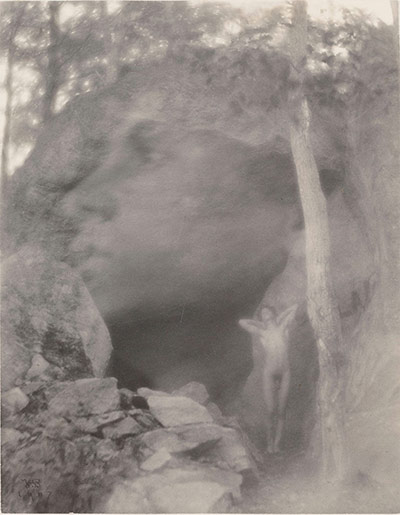

This photograph emulates symbolist artists such as Odilon Redon and Gauguin.

By mixing ordinary photographs, it creates an extraordinary ethereal vision

Photograph: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York Photograph: Action images