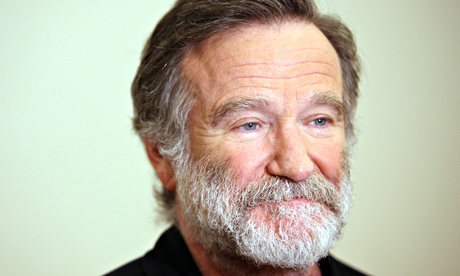

Although the recent death of Robin Williams generated millions of tweets, people’s fascination with celebrity deaths is far from new. The Egyptians and Mayans built colossal monuments to worship their royals; the Greeks and Romans organised massive funerals to commemorate poets and military heroes. In the 19th century, Victor Hugo’s funeral drew millions of people to the streets of Paris, and we all remember Diana’s funeral.

Given that celebrities are primarily known for their public personas, it is understandable that their deaths evoke displays of public mourning. When celebrities pass away, they often attract more media attention than while alive. As a recent study concluded: “The death of a celebrity appears to strongly elevate the celebrity’s status and increase the value of their products.” For example, Forbes estimates Michael Jackson earned $160m last year – compared to $125m for Madonna, the highest-earning living celebrity – while Elvis Presley still earns around $50m each year.

For devoted fans, celebrity deaths may be experienced with the same emotional intensity as the loss of close friends. This is quite remarkable since the relationship between fans and celebrities is unidirectional and parasocial. As Lord Byron said: “[Fame] is the advantage of being known by people of whom you yourself know nothing, and for whom you care as little.” To fans the relationship is as real and intimate as any relationship can be, if not more.

Celebrities can shape the values, attitudes and personalities of their fans, which is most noticeable in the case of pathological celebrity worship, where fans are absorbed in an imaginary relationship with the celebrity, to a point where celebrity deaths can cause depression in their fans.

For the general public, celebrity deaths are a much more superficial event. First, when deaths are unnatural and dramatic, they act as a powerful reminder of the tragic side of fame, and that money and career success don’t guarantee happiness. This is hardly news, but it is easily forgotten in the superficial view of entertainment.

Second, when celebrities are artists, their deaths evoke the mysterious relationship between creativity and mental illness. Although this topic has attracted considerable popular and academic interest for many decades, there is now evidence for the idea that psychiatric conditions, especially bipolar disorders, are more prevalent among creative people and their families.

Third, the internet has the capacity to turn any event, including death, into a social trend. Content becomes more interesting as it becomes more sharable, rather than vice versa as Kony 2012, Gangnam Style, and the ALS ice bucket challenge, have all demonstrated.

It is a wonderful act of solidarity and empathy to mourn celebrities, but it also highlights our indifference to the death and suffering of those who are not famous.

Psychologists have often distinguished between grief and mourning: the former concerns how we feel internally when someone dies; the latter concerns the public display of those feelings. In that sense, the unusual thing about public reactions to celebrity deaths is that they may often represent mourning without real grief. It seems, therefore, less a symptom of collective suffering than polite cultural etiquette and mindless media consumption. Conversely, when people’s mourning is accompanied by genuine grief – such as in the case of real losses – social media may act as a social buffer for people’s loneliness. When others’ see our mourning, social media can have a positive effect on mourners by evoking startling altruistic responses from others.

Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic is a professor of business psychology at University College London and vice president of research and innovation at Hogan Assessment Systems. He is co-founder of metaprofiling.com and author of Confidence: Overcoming Low Self-Esteem, Insecurity, and Self-Doubt.

Read more stories like this:

• Sharing the (self) love: the rise of the selfie and digital narcissism

• Kim Kardashian: why we love her and the psychology of celebrity worship

To get weekly news analysis, job alerts and event notifications direct to your inbox, sign up free for Media Network membership.

All Guardian Media Network content is editorially independent except for pieces labelled ‘Advertisement feature’. Find out more here.